====== 1-203 ======

Kenneth M. KaufmanManatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP © 2017 Kenneth M. Kaufman Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP Attachment 4: © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. Reprinted from WestlawNext with the permission of Thomson Reuters. Attachment 5: Reprinted from Federal Reporter, 3d with the permission of Thomson Reuters. Attachment 7: © 2015 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. Reprinted from WestlawNext with the permission of Thomson Reuters. Attachment 9: © 2014 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. Reprinted from Westlaw with the permission of Thomson Reuters. If you find this article helpful, you can learn more about the subject by going to www.pli.edu to view the on demand program or segment for which it was written. |

====== 1-205 ======

| I. Introduction |

A. | Convergence Issues |

| II. Current Market Trends and the Impact of Digital Media and Distribution |

A. | Rights in Content and in Software | ||||||||

B. | Interactive vs. Static | ||||||||

C. | Perfect Digital Copies | ||||||||

D. | Scalable | ||||||||

E. | Territorial vs. Non-Territorial | ||||||||

F. | Durable | ||||||||

G. | Searchable | ||||||||

H. | Users vs. Publishers | ||||||||

I. | Emergence of Social Media Platforms | ||||||||

J. | User-Generated Content | ||||||||

K. | Short-Form Video | ||||||||

L. | Impact of DVR’s | ||||||||

M. | Rethinking of Roles of “Gatekeepers” | ||||||||

N. | Enhanced Importance of Intellectual Property Protection | ||||||||

O. | Licensing and Administration of Rights | ||||||||

P. | Migration from Linear to On-Demand | ||||||||

Q. | Migration to Online and Mobile Platforms | ||||||||

R. | Emergence of Cloud Computing | ||||||||

S. | New Digital Rights

| ||||||||

T. | Rapid Evolution of Business, Monetization and Advertising Models

| ||||||||

U. | Hybrid Agreements | ||||||||

====== 1-206 ====== | |||||||||

V. | Aggregation of Content and Distribution | ||||||||

W. | Public Policy Issues

| ||||||||

X. | Technology vs. Law | ||||||||

Y. | Questioning of Traditional Principles of Copyright Law

| ||||||||

Z. | Emerging Solutions

| ||||||||

| III. Rights in Preexisting Content |

A. | Post-1977 vs. Pre-1978 Works |

B. | Post-1972 vs. Pre-1972 Sound Recordings |

| IV. Exclusive Rights of Copyright Owners |

A. | Reproduction in Copies or Phonorecords | ||||

B. | Preparation of Derivative Works | ||||

C. | Distribution of Copies or Phonorecords | ||||

D. | Public Performance (for Certain Works) | ||||

E. | Public Display (for Certain Works) | ||||

F. | Public Performance of Sound Recordings by Means of Digital Audio Transmissions

|

====== 1-207 ======

| V. Structuring the Acquisition of Rights in Content |

A. | License

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

B. | Assignment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

C. | Work Made for Hire

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

D. | Requirements for Work Made for Hire

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

E. | California Issues

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

F. | Back-Up Assignment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

G. | International Treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| VI. Termination of Transfers and Licenses |

A. | 17 U.S.C. §§ 203, 304(c) and 304(d) | ||||||||||||||||||

B. | Earliest Effective Date of Termination (Based on Whether Grant Was Executed Before or After January 1, 1978)

| ||||||||||||||||||

C. | Section 203 Terminations

| ||||||||||||||||||

D. | Section 304 Terminations

| ||||||||||||||||||

E. | Impact on Derivative Works | ||||||||||||||||||

F. | Termination may be effected “notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary” | ||||||||||||||||||

G. | Notice | ||||||||||||||||||

H. | Siegel v. Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., 542 F. Supp. 2d 1098 (C.D. Cal. 2008), 658 F. Supp. 2d 1036 (C.D. Cal. 2009), and 690 F. Supp. 2d 1048 (C.D. Cal. 2009) | ||||||||||||||||||

I. | DC Comics v. Pacific Pictures Corp., No. 10-3633, 2012 WL 4936588 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 17, 2012) | ||||||||||||||||||

J. | Larson v. Warner Bros Entertainment, Inc., Nos. 13-56243, 13-56244, 13-56257, 13-56259, 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 2507 (9th Cir. Feb. 10, 2016) | ||||||||||||||||||

====== 1-210 ====== | |||||||||||||||||||

K. | Marvel Characters, Inc. v. Simon, 310 F.3d 280 (2d Cir. 2002) | ||||||||||||||||||

L. | Scorpio Music S.A. v. Willis, No. 11-1557, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 63858 (S.D. Cal. May 7, 2012) | ||||||||||||||||||

M. | Scorpio Music Black Scorpio S.A. v. Willis, No. 11-1557, 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 124000 (S.D. Cal. Sept. 15, 2015) | ||||||||||||||||||

N. | Baldwin v. EMI Feist Catalog, Inc., 805 F.3d 18 (2d Cir. 2015) | ||||||||||||||||||

O. | Grants Entered Into Before 1978 Where Work Created After 1977

| ||||||||||||||||||

| VII. License vs. Sale in Digital Media Agreements |

A. | F.B.T. Productions, LLC v. Aftermath Recordings, 621 F.3d 958 (9th Cir. 2010) |

| VIII. Social Media and User-Generated Content |

A. | Characteristics

| ||||||||||||||||||||

B. | Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) Safe Harbor, 17 U.S.C. § 512(c)

| ||||||||||||||||||||

C. | Communications Decency Act of 1996 (CDA)

| ||||||||||||||||||||

D. | Digital Media Licenses: Terms of Use/End User License Agreements

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| IX. Contract Issues and Negotiating Points – Content and Entertainment Licensing Agreements |

A. | Parties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

B. | Media Covered by the Grant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

C. | Formats/Platforms/Devices Covered by the Grant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

D. | Specific Rights Granted | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

E. | Services to Be Provided | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

====== 1-212 ====== | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

F. | Term of License

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

G. | Post-Term Rights

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

H. | Exclusivity

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

I. | Territory/Languages

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

J. | Security

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

K. | Compensation/Consideration

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

L. | Collection, Ownership and Use of User Data | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

M. | Ownership and Use of User-Generated Content | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

N. | Most Favored Nations (MFN) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

O. | Representations, Warranties and Indemnities | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

P. | Limitation of Liability | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Q. | Scope of Rights Originally Granted to Licensor

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

R. | Approval Rights

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

S. | Changes in Licensed Material

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

T. | Derivative Works

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

====== 1-214 ====== | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

U. | Rights in Technology | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

V. | Ancillary and Subsidiary Rights

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

W. | Reserved Rights

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

X. | Credit/Billing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Y. | Co-Branding/Joint Activities | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Z. | Relationship to Other Agreements | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AA. | Key-Person Provision | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BB. | Name and Likeness Rights

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CC. | Accountings and Audit Rights | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

DD. | Remedies

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

EE. | Insurance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FF. | Responsibility for Music and Other Content Clearances | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

GG. | Union and Guild Payments and Residuals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

HH. | Use of Trademarks | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

II. | Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

JJ. | Assignability and Change of Control | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

KK. | Buyout/Exit Provisions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

LL. | Ability to Sublicense or Syndicate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

MM. | Termination | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NN. | Governing Law | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

OO. | Dispute Resolution | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

PP. | Confidentiality | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

====== 1-215 ======

| X. Music Licensing in Digital Media |

A. | Musical Works vs. Sound Recordings | ||||||||||||||||||

B. | Public Performance License (Musical Works)

| ||||||||||||||||||

C. | Public Performance License (Sound Recordings)

| ||||||||||||||||||

D. | Mechanical License

| ||||||||||||||||||

E. | Download vs. Public Performance

| ||||||||||||||||||

F. | Synchronization License | ||||||||||||||||||

G. | Derivative Work License | ||||||||||||||||||

H. | Public Display License | ||||||||||||||||||

I. | Master Use License | ||||||||||||||||||

| XI. Name and Likeness Rights |

A. | Rights of Privacy and Publicity

|

| XII. Fair Use |

A. | Purpose and Character of the Use |

B. | Nature of the Copyrighted Work |

C. | Amount and Substantiality of Portion Used |

D. | Effect on Potential Market for Underlying Work |

E. | Sony Corp. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984) |

F. | Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994) |

G. | Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television, Inc., 126 F.3d 70 (2d Cir. 1997) |

====== 1-217 ====== | |

H. | Cariou v. Prince, No. 11-1197, 2013 U.S. App. LEXIS 8380 (2d Cir. Apr. 25, 2013) |

I. | Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust, 755 F.3d 87 (2d Cir. 2014) |

J. | White v. West Publishing Corp., No. 12-1340, 2014 WL 3385480 (S.D.N.Y. July 11, 2014) |

K. | Fox Broadcasting Co. Inc. v. Dish Network L.L.C., 747 F.3d 1060 (9th Cir. 2014), on remand, No. 12-4529, 2015 U.S. Dist. Lexis 23496 (Jan. 12, 2015) |

L. | Fox News Network, LLC v. TVEyes, Inc., No. 13-5315, 2015 WL 5025274 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 25, 2015) |

M. | Galvin v. Illinois Republican Party, 130 F. Supp. 3d 1187 (N.D. Ill. 2015) |

N. | Authors Guild v. Google, Inc., 804 F.3d 202 (2d Cir. 2015) |

O. | Cambridge University Press v. Becker, No. 1:08-CV-01425-ODE (N.D. Ga. Mar. 31, 2016), appeal docketed, Aug. 26, 2016 |

P. | Lenz v. Universal Music Corp., 815 F.3d 1145 (9th Cir. 2016) |

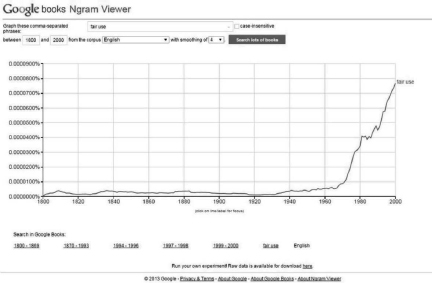

Q. | TCA Television Corp. v. McCollum, No. 1:16-CV-0134 (2d Cir. Oct. 11, 2016) |

| XIII. Public Domain |

A. | Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd., No. 14-1128, 2014 WL 2726187 (7th Cir. June 16, 2014) |

| XIV. Online Copyright Infringement Actions |

A. | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913 (2005) |

B. | Cartoon Network LP, LLLP v. CSC Holdings, Inc., 536 F.3d 121 (2d Cir. 2008) |

C. | Arista Records, LLC v. Launch Media, Inc., 578 F.2d 148 (2d Cir. 2009) |

D. | Viacom International Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., 676 F.3d 19 (2d Cir. 2012), on remand, No. 07-2103, 2013 WL 1689071 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 18, 2013) |

====== 1-218 ====== | |

E. | American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. v. Aereo, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2498 (2014) |

F. | American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. v. Aereo, Inc., No. 12-1540, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 150555 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 23, 2014) |

G. | Fox Television Stations, Inc. v. FilmOn X, LLC, No. 12-6921 (C.D. Cal. July 16, 2015) |

H. | Fox Television Stations, Inc. v. FilmOn X, LLC, No. 13-758, 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 161304 (D.D.C. Dec. 2, 2015) |

| XV. Union and Guild Issues |

| XVI. Current Public Policy and Technology Issues |

A. | Piracy |

B. | Digital Rights Management |

C. | Interoperability |

D. | Net Neutrality |

E. | Retransmission Consent |

F. | Definition of MVPD (Multichannel Video Programming Distributor) |

| XVII. Previous “New” Media |

====== 1-219 ======

CONTENT LICENSE AGREEMENT

THIS LICENSE AGREEMENT (the “Agreement”) is made and entered into as of the _____ day of _______________, 2015 (the “Effective Date”), by and between _________________________ (“Licensor”), a __________ corporation having its principal place of business at _________________________________________________________, and _______________________________ (“Licensee”), a _____________ corporation having its principal place of business at ______________________________. WHEREAS, Licensor publishes magazines and other print publications relating to ______________________;

WHEREAS, Licensee is a media, entertainment and information provider that uses the Internet to provide entertainment, news and information;

WHEREAS, Licensee desires to obtain from Licensor the right to use and distribute certain content developed by Licensor as defined herein; and

WHEREAS, Licensor is willing to grant such rights to Licensee in accordance with the terms and conditions of this Agreement;

NOW, THEREFORE, in consideration of the terms and conditions set forth herein, the parties hereto hereby agree as follows:

| 1. Definitions |

1.1 | “Licensor Content” shall mean and be comprised of certain mutually agreed-upon content including but not limited to the information contained in the magazines and other print publications attached as Exhibit A hereto, and other specific information when mutually agreed upon or specifically referenced in this Agreement. |

1.2 | “Licensor Web Site” shall mean the site currently located at http:\\www.Licensor.com. |

1.3 | “Licensee Web Site” shall mean the site currently located at http:\\www.Licensee.com. |

1.4 | “Online Services” shall mean any systems for distributing or otherwise making available content via transmission, broadcast, public display, or other forms of delivery, whether direct or indirect, to end users, whether over telephone lines, cable television systems, optical fiber connections, cellular telephones, satellites, wireless ====== 1-220 ====== |

| 2. License Grant |

2.1 | Except as set forth in paragraph 3.1 of this Agreement, and subject to the provisions of paragraphs 2.2 and 4 below, Licensor hereby grants to Licensee a nonexclusive worldwide license during the Term of this Agreement to do the following with respect to the Licensor Content which will appear on Licensee’s website unless otherwise stated herein:

| ||||||

2.2 | As a condition of the licenses granted pursuant to paragraph 2.1, Licensee shall require that all such use, reproduction, copying, distribution, transmission, advertising, marketing, display and performance of Licensor Content include the Licensor logo and a Licensor copyright notice, and, if applicable, links back to Licensor’s website as set forth in Paragraph 5 of this Agreement. |

| 3. Licensor Obligations |

On or before the Effective Date, Licensor shall provide to Licensee the Licensor Content referred to in Exhibit A. Licensor shall deliver any updates or upgrades to Licensor Content within thirty (30) days of such update or upgrade’s publication in any form, including publication on Licensor’s website. Licensor shall deliver the Licensor Content in HTML format via FTP. Licensee reserves the right to reject any Licensor Content submitted by Licensor within seven (7) days of Licensee’s receipt thereof, such rejection not to be unreasonable. In the event that Licensee rejects Licensor Content, Licensor shall use reasonable efforts to submit alternative content within seven (7) days of Licensee’s rejection.

====== 1-221 ======

| 4. License Restrictions |

4.1 | Licensee shall not market, distribute, sublicense, lease or rent the Licensor Content on a stand-alone basis (i.e., other than as part of the Licensee Online Services). |

4.2 | Licensee shall not edit, modify or revise the Licensor Content in any manner whatsoever without first obtaining Licensor’s prior written consent thereto, which may be granted or withheld in Licensor’s sole discretion. |

4.3 | Any and all rights not specifically granted herein to Licensee are reserved by Licensor. |

4.4 | Licensor and Licensee agree to prominently post a mutually approved disclaimer at the bottom of each item of Licensor Content submitted hereunder. |

| 5. Co-Branding/Promotion |

Licensor and Licensee agree to work together to create certain co-branded banners and/or pages on the _____________ website and other co-branded advertising and joint promotions. Licensee shall use its good-faith efforts to promote Licensor as part of its co-branded advertising and promotions related to the _____________ website. Licensor shall use its good-faith efforts to promote the ___________ website, including but not limited to providing a graphic link to the Licensee home page and a description of Licensee and its services in a mutually agreeable format on the home page of Licensor’s website. On all pages containing the Licensor Content, Licensee shall provide a textual link to a designated portion of Licensor’s On-line Services.

| 6. Exclusivity |

Notwithstanding anything to the contrary herein, Licensor shall not provide any Licensor Content to any third-party provider of online services whose primary focus is providing entertainment, news and information about ______________________________. Nothing herein shall prohibit Licensor from providing Licensor Content on Licensor’s website.

====== 1-222 ======

| 7. Joint Projects |

Licensee and Licensor may, at a later date, agree to co-produce certain co-branded productions regarding subjects of public interest, provided that the parties are able to mutually agree upon the subjects, resources, content required by each party, the host site, and the time frame for each such co-production. Neither party shall be obligated to participate in any such co-production(s) during the Term of this Agreement.

| 8. Payment |

No payments shall be owed by either party to the other for the license granted herein. Each party shall be responsible for any expenses incurred by such party pursuant to this Agreement, and each party will retain any other revenue generated from its respective website or otherwise. The parties shall negotiate in good faith regarding possible investments and/or revenue participation in co-branded productions which the parties may agree to produce pursuant to paragraph 6 above.

| 9. Warranties and Indemnities |

9.1 | Warranties.

| ||||

9.2 | EXCEPT AS SET FORTH HEREIN, ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, ARE EXPRESSLY EXCLUDED AND DECLINED. EACH PARTY DISCLAIMS ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES, PROMISES AND CONDITIONS OF MERCHANTBILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, TITLE AND/OR NON-INFRINGEMENT, WHETHER AS TO ANY CONTENT OR SERVICES RENDERED BY LICENSEE OR LICENSOR AND/OR THE TECHNOLOGY DEPLOYED IN CONNECTION THEREWITH. EXCEPT AS SET FORTH HEREIN, LICENSEE MAKES NO REPRESENTATION THAT THE OPERATION OF LICENSEE’S WEBSITE WILL BE UNINTERRUPTED OR ERROR-FREE, AND LICENSEE WILL NOT BE LIABLE FOR THE CONSEQUENCES OF ANY INTERRUPTIONS OR ERRORS. | ||||

9.3 | IN NO EVENT SHALL EITHER PARTY BE LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, OR SPECIAL DAMAGES WHATSOEVER, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION DAMAGES FOR LOSS OF BUSINESS PROFITS, BUSINESS INTERRUPTION, LOSS OF BUSINESS INFORMATION, AND THE LIKE, ARISING OUT OF THE USE OF OR INABILITY TO USE THE CONTENT OR LOGOS REFERRED TO IN THIS AGREEMENT, EVEN IF THE PARTY HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. | ||||

9.4 | Indemnities. Each party (the “indemnifying party”) shall, at its expense and at the other party’s (the “indemnified party’s”) request, defend any third-party claim or action brought against the indemnified party, and the indemnified party’s directors, officers, employees, licensees, agents, attorneys and independent contractors, (i) relating to the indemnifying party’s website, content, network, products, services, and accessories or the marketing thereof, and (ii) to the extent it is based upon a claim that, if true, would constitute ====== 1-224 ====== |

| 10. Intellectual Property |

Each party retains all rights, title and interest, including without limitation rights of trademark and copyright, in all of its property, including but not limited to trade names, trademarks, service marks, symbols, identifiers, formats, designs, devices, identifiers, and proprietary products, services and information owned by such party.

| 11. Independent Development |

Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed as restricting Licensee’s ability to acquire, license, develop, manufacture or distribute for itself, or have others acquire, license, develop, manufacture or distribute for Licensee, similar content, services, or technology performing the same or similar functions as the content, services or technology contemplated by this Agreement, or to market and distribute such similar technology in addition to, or in lieu of, the content, services, or technology contemplated by this Agreement.

| 12. Term and Termination |

12.1 | The Term of the Agreement shall commence on the Effective Date and continue for _____ (_) years unless otherwise amended, extended, or terminated. (“Term”). The Agreement shall be automatically renewed for subsequent one (1)-year periods, unless either party shall provide written notice of termination to the other no later than sixty (60) days prior to the expiration date of the Agreement. |

12.2 | This Agreement may be terminated by either party prior to its natural expiration if any of the following events of default occurs: ====== 1-225 ====== |

12.3 | Either party may terminate this Agreement at any time during the Term of the Agreement, for any reason, by providing written notice to the other party of such termination at least ninety (90) days in advance thereof. |

| 13. Notices |

All notices and requests in connection with this Agreement shall be deemed given as of the day they are received via messenger or delivery service, or three (3) days after they are deposited in the United States mail, postage prepaid, by certified or registered mail, return receipt requested, and addressed as follows:

====== 1-226 ======

Notices to Licensee: | Notices to Licensor: |

Licensee | Licensor |

A party may change its address by giving the other party written notice thereof in the manner set forth above.

| 14. General |

14.1 | Entire Agreement. This Agreement constitutes the entire agreement between the parties with respect to the subject matter hereof and merges all prior and contemporaneous communications. It may not be modified except by a written agreement dated subsequent to the date of this Agreement and signed on behalf of Licensee and Licensor by their respective duly authorized representatives. |

14.2 | Assignment. This Agreement may not be assigned by either party without the other party’s prior written consent, and any purported assignment without such consent shall be null and void. Except as otherwise provided, this Agreement shall be binding upon and inure to the benefit of the parties’ successors and permitted assigns. Notwithstanding the foregoing, either party may, without the other party’s consent, assign this Agreement to (i) a parent, subsidiary, affiliate, division or corporation controlling, controlled by or under common control with the assigning party; (ii) a successor corporation related to the assigning party by merger, consolidation, nonbankruptcy reorganization or government action; or (iii) a purchaser of all or substantially all of the assigning party’s assets. |

14.3 | Attorneys’ Fees. In any action or suit to enforce any right or remedy under this Agreement or to interpret any provision of this Agreement, the prevailing party shall be entitled to recover its costs, including reasonable attorneys’ fees. |

14.4 | Confidentiality. Each party shall hold in strictest confidence, shall not use or disclose to any third party, and shall take all necessary precautions to secure, any Confidential Information of the other party. Disclosure of such information shall be restricted solely to employees, agents, attorneys, consultants and representatives who ====== 1-227 ====== |

14.5 | Choice of Law. This Agreement shall be construed in accordance with the laws of the State of ______________, and the parties consent to jurisdiction and venue in the state and federal courts sitting in __________________. |

14.6 | Severability. If for any reason a court of competent jurisdiction finds any provision of this Agreement, or portion thereof, to be unenforceable, that provision of the Agreement shall be enforced to the maximum extent permissible so as to effect the intent of the parties, and the remainder of this Agreement shall continue in full force and effect. Failure by either party to enforce any provision of this Agreement shall not be deemed a waiver of future enforcement of that or any other provision. This Agreement has been negotiated by the parties and their respective counsel and shall be interpreted fairly in accordance with its terms and without any strict construction in favor of or against either party. |

14.7 | Waiver. No waiver of any breach of any provision of this Agreement shall constitute a waiver of any prior, concurrent or subsequent breach of the same or any other provision hereof, and no waiver shall be effective unless made in writing and signed by an authorized representative of the waiving party. |

====== 1-228 ====== | |

14.8 | Headings. The section headings used in this Agreement are intended for convenience only and shall not be deemed to supersede or modify any provisions. |

14.9 | No Offer. This Agreement does not constitute an offer by either party and it shall not be effective until signed by both parties. |

14.10 | Equitable Relief. Licensor expressly disclaims any rights it may have either in contract or in tort to seek equitable relief against Licensee for a breach of this Agreement, including but not limited to temporary restraining orders, preliminary injunctions or specific performance. Licensor’s sole remedy for any alleged breach of this Agreement shall be to seek monetary damages in a court of competent jurisdiction. |

14.11 | Execution in Counterparts. This Agreement may be executed in any number of counterparts, each of which when so executed and delivered shall be deemed an original, and such counterparts together shall constitute one instrument. |

14.12 | No Joint Venture. Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed as creating an employer-employee relationship, a partnership, or a joint venture between the parties. |

WHEREBY, the parties have executed this Agreement as of the Effective Date.

====== 1-229 ======

PRODUCTION COMPANY, INC.

[address]

As of ________________, 2015

Ms. Jane Q. Owner

[address]

Dear Ms. Owner:

The following shall constitute the agreement between you (“Owner”) and Production Company, Inc., a _________ corporation (“Producer”), regarding the literary property entitled “The Book”, together with all ideas, themes, names, titles, plots, concepts, illustrations, descriptions, characters, characterizations, events and incidents contained therein or related thereto, and all versions and adaptations thereof and all copyrights and trademark rights relating thereto (all of the foregoing being collectively referred to herein as the “Property”):

1. | Grant of Option. In consideration of the payment to Owner of ________________ Dollars ($____) upon the complete execution hereof, Owner hereby grants to Producer the exclusive and irrevocable option (the “Option”) to purchase from Owner, for the purchase price set forth in this Agreement, all rights herein set forth in and to the Property. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2. | Exercise of Option. Producer may exercise the Option at any time during the period (the “Option Period”) commencing on the date hereof and ending on the date which is one (1) year after the date hereof. Producer may extend the Option Period for an additional consecutive period of one (1) year by giving notice to Owner of such extension and by paying Owner the sum of _____________ Dollars ($____) at any time prior to the date the Option Period would otherwise expire. Any reference herein to the Option Period shall be deemed to refer to the Option Period as the same may be extended. In the event of the occurrence of one or more events of force majeure, or in the event that any claim is asserted involving any of the representations, warranties, covenants or agreements of Owner herein, the Option Period shall be deemed suspended for a period equal to the duration(s) of the said event(s) of force majeure or until such claim is settled or reduced to final judgment in a court of competent jurisdiction, and the date for exercise of the Option ====== 1-230 ====== | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3. | Production Activities. Owner acknowledges that Producer may, during the Option Period, undertake development, pre-production and/or production activities in connection with any of the rights to be acquired by Producer hereunder if the Option is exercised, including, without limitation, the preparation and submission of treatments, teleplays and/or screenplays based upon the Property. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

4. | Rights Granted. Upon Producer’s exercise of the Option, the following rights in and to the Property shall automatically vest in Producer, its successors, representatives, licensees and assigns, solely and exclusively and forever:

Owner acknowledges that all rights in and to all Productions hereunder shall be the sole and absolute property of Producer for any and all purposes whatsoever in perpetuity. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

5. | Reserved Rights. Owner hereby reserves and does not grant to Producer, subject to the provisions of Paragraphs 4 and 6 hereof, print publication rights (other than novelization rights) and legitimate stage rights in the Property. Notwithstanding the foregoing, ====== 1-232 ====== | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

6. | Restrictions on Reserved Rights. It is understood that Owner shall have the right to write, publish and permit to be published print publications based on the Property, provided, however, that Owner shall not exercise or grant to any Person at any time, with respect to any such publication(s), any of the rights herein granted to Producer, and provided further that Producer shall have the right, without the payment of additional compensation to Owner, to use material contained in any such publication(s) in any manner as Producer shall determine in connection with the exercise by Producer of its rights hereunder. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

7. | Consideration. If Producer exercises the Option, as full and complete consideration for all rights, licenses and privileges granted by Owner to Producer hereunder, and for all representations, warranties, indemnities and agreements of Owner herein, Producer shall pay to Owner the following:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

8. | Credit.Owner shall be accorded credit on all positive prints of any television series or other Production(s) produced in the exercise of the rights granted to Producer herein, in substantially the following form: “Based on the book ‘The Book’ by Jane Q. Owner.” All aspects of the aforesaid credit, including, without limitation, the size, style and placement thereof, shall be determined by Producer in its sole discretion. No casual or inadvertent failure of Producer or any third party to comply with the provisions of this paragraph shall constitute a breach of this Agreement. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

9. | Representations and Warranties. Owner hereby represents and warrants that: (a) Owner is the sole author of the Property and all elements thereof; (b) Owner is the sole and exclusive owner and proprietor throughout the universe of the Property and any and all rights therein; (c) Owner has the full right, power and authority to enter into this Agreement and to grant to Producer all the rights herein stated to be granted; (d) no motion picture, television, radio, dramatic or other version or adaptation of the Property has heretofore been produced, performed, authorized to be produced or performed, or copyrighted or registered for copyright, in any country of the world; (e) the Property is wholly original with Owner and has not been copied or adapted from any literary work or other work; (f) nothing contained in the Property shall infringe upon or in any way violate the copyright, right of privacy, right of publicity, right against defamation, trademark or trade name rights, or any other personal or proprietary right of any Person; (g) Owner has not granted to any Person nor will Owner grant to any Person any right or the option to acquire any right which would conflict or interfere with any of the rights granted to Producer hereunder or which would impair or diminish the value of the rights granted to Producer here-under, nor has Owner in any manner encumbered any of said rights; (h) neither the exercise of the Option nor the exploitation of any of the rights granted to Producer herein will infringe upon or violate any rights of any Person whatsoever; (i) neither the Property nor any part thereof is in the public domain anywhere in the world; (j) the Property is entirely fictional and does not portray any real persons or other entities whether living or dead; (k) the Property was registered for copyright in the United States Copyright Office ====== 1-235 ====== | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

10. | Indemnity. Owner will indemnify and hold harmless Producer and Producer’s licensees, representatives, successors and assigns, and the employees, officers, directors, agents, representatives, attorneys and shareholders of each of them, from and against any and all claims, actions, damages, losses, liabilities, costs and expenses (including reasonable attorneys’ fees) arising from or in connection with any claim of breach of any warranty, representation, covenant, undertaking or agreement made by Owner in this Agreement. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

11. | No Injunction. All the rights, licenses, privileges and property herein granted to Producer are irrevocable and not subject to rescission, restraint, or injunction under any or all circumstances. In the event of any breach of this Agreement or any portion thereof by Producer (including, without limitation, failure to accord credit pursuant to Paragraph 8 hereof), Owner’s sole remedy shall be an action at law for damages, if any; and in no event shall Owner have the right to injunctive relief or to restrain or otherwise interfere with the distribution or exhibition of any Production or the exercise of any rights granted to Producer herein. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

12. | Other Documents. At the request of Producer or its attorneys, Owner shall promptly execute and deliver any and all additional documents and/or instruments, including without limitation a short-form assignment for purposes of recording in the Copyright Office, and shall do any and all things necessary or desirable to evidence Producer’s rights hereunder or otherwise to effectuate the intent and purposes of this Agreement. Should Owner fail to so execute and deliver any such document(s) or instrument(s) or fail to do anything necessary or desirable to effectuate the purposes of this Agreement within five (5) business days of Producer’s request therefor, Producer is hereby irrevocably appointed as Owner’s true and lawful attorney-in-fact (such appointment being coupled with an interest) with the right, but not the obligation, to execute and/or record such ====== 1-236 ====== | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

13. | No Obligation. In the event that Producer shall exercise the Option, Producer shall have no obligation to produce any production(s) or otherwise to exploit the Property or any part(s) or element(s) thereof, and Producer’s sole obligation in such regard shall be the payment of the applicable purchase price as specified in Paragraph 7(a) hereof. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

14. | Miscellaneous. This Agreement may not be changed or modified, nor may any provision hereof be waived, except in a writing signed by the parties hereto. This Agreement shall be construed in accordance with the internal laws of the State of _____________ applicable to agreements entered into and wholly to be performed within said state, without regard to conflicts of laws principles. The state and federal courts having jurisdiction over _________ County, ____________ shall have exclusive jurisdiction over any and all disputes arising under this Agreement or related to its subject matter. Producer shall have the right to assign this Agreement and all or any part of Producer’s rights hereunder to any Person, without limitation, and upon any such assignment Producer shall be relieved of its obligations hereunder. Owner may not assign this Agreement or any rights hereunder without Producer’s prior written consent, and any purported assignment by Owner shall be null and void. As used herein, the term “Person” shall include any natural person, firm or corporation or any group of individuals, firms or corporations, or any other entity. This Agreement shall be binding upon and inure to the benefit of the parties hereto and their respective heirs, administrators, representatives, successors, licensees, and permitted assigns. By entering into this Agreement, Producer does not waive any rights it would have as a member of the general public in the absence of this Agreement. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

15. | More Formal Agreement. The parties intend to enter into a more formal agreement incorporating the terms and conditions hereof and other standard terms and conditions for agreements of this type. Until such time, if ever, as a more formal agreement is executed by the parties, this Agreement shall bind the parties and shall contain the entire understanding of Producer and Owner regarding its subject matter, and shall supersede any and all prior discussions, negotiations and understandings relating to its subject matter. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

====== 1-237 ======

If the foregoing terms and conditions are in accordance with your understanding of our agreement, kindly indicate your acceptance thereof by signing below.

Very truly yours, PRODUCTION COMPANY, INC. | |

By:___________________ Title:__________________ | |

ACCEPTED AND AGREED TO: | |

________________ |

====== 1-239 ======

LICENSE AGREEMENT FOR SUBSCRIPTION VIDEO ON DEMAND DELIVERY

This License Agreement for SVOD Delivery (“Agreement”) is entered into as of the ___ day of ________, 2017 (the “Effective Date”) by and between ______________________, a _________ corporation (“Licensee”) and __________________, a _________ corporation (“Distributor”).

Recitals

Licensee owns and operates a subscription entertainment service providing its members with access to motion pictures, television and other digital entertainment products (collectively, “Titles”).

Distributor is in the business of distributing certain Titles.

Licensee and Distributor desire to enter into an agreement whereby Distributor will grant Licensee a limited, nonexclusive license to distribute those Titles set forth in Schedule A, within the United States, its territories and possessions (the “Territory”), all in accordance with the terms and conditions set forth below.

Agreement

In consideration of the mutual promises contained herein and such other good and valuable consideration, the parties hereto agree as follows:

| 1. Definitions |

1.1 | “Approved Devices” means a Personal Computer, Portable Device, Set-Top Box or Other Device that in each instance supports the DRM required pursuant to Section 2.3 and is capable of accessing the Licensee Service belonging to or in the possession of an Authorized User. |

1.2 | “Authorized User” means a home or private residential unit authorized by Licensee to receive all or any part of the Licensee Service solely on a subscription basis. |

1.3 | “Home Video Device” means all formats of “hard goods” self contained video devices that themselves embody (without need for further transfer of data or activation or authorization to enable playback for exhibition) a motion picture or other programming for exhibition by means of a playback device (i.e., tangible, fixed data-carrying media) now known or hereafter known or devised, including, ====== 1-240 ====== |

1.4 | “Interactive” means any exhibition of a Title by means of a viewing device (including any Approved Device) in which the end user or viewer has the ability to (i) choose the presentation of audio and/or video portions of the Title, including, without limitation, by means of determining how the audio and/or video portions are exhibited (e.g., different camera angles, audio tracks or background music) and/or manipulating, altering or affecting the participants, setting, progression of actual events as they occur, the outcome, or other key elements of the program, and/or (ii) engage in two-way transmissions that include the ability for the end user or viewer to access information, products and services related to the audiovisual signals, including without limitation by utilizing “hyperlinks” or other “click-through” options to link directly to an Internet web-page or similar location, or the activation of on-screen commands to access such pages or locations, in each case that offer such information, products, or services. |

1.5 | “Licensee Service” shall mean the point-to-point, streaming or downloaded content subscription distribution service presently entitled “____________” owned and operated by Licensee and providing its Authorized Users with on-demand access utilizing Permitted Means to the exhibition of motion pictures, television and other entertainment products in a variety of exhibition formats, including by means of high definition television to the extent expressly permitted hereunder, on an SVOD basis. |

1.6 | “Other Device” means an Internet-connected television monitor, DVD player, game console, media extender or similar device supporting the approved DRM. |

1.7 | “Permitted Means” means the encrypted transmission of a Title by means of the Internet or any other form of digital transmission utilizing internet protocol, including without limitation traditional and TCP/IP protocols, from Licensee-secured servers (utilizing optical fiber, DSL, coaxial cable or any other delivery system), to an Authorized User’s individual Approved Device located within ====== 1-241 ====== |

1.8 | “Personal Computer” means an IP-enabled desktop or laptop computer supporting the approved DRM with a hard drive, keyboard and monitor, and shall not include any other IP-enabled devices such Portable Devices, personal video recorders, set-top boxes, or the like. |

1.9 | “Portable Device” means a handheld audio/video playback device (e.g., iPod), cellular phone, “Smartphone”, pager, camera, personal digital assistant (including BlackBerrys and Treos and any successors thereto) and other mobile devices now known or hereafter devised that is capable of intelligibly playing back or exhibiting a Title, by being connected to the Internet or any other device (i.e., on a “side load” or “tethered” basis). |

1.10 | “Running Fee” shall have the meaning set forth in Section 4.2.2 below. |

1.11 | “Set-Top Box” means a set-top device which is made available to Authorized Users of the Licensee Service supporting the approved DRM and required for the reception, decoding and display of audio visual programming on a television set or a video monitor (which shall not include a display on a mobile phone) associated with such Set-Top Box. “Set-Top Box” shall not include a Personal Computer or Portable Device. |

1.12 | “Source Material” shall mean the source files of the Titles, artwork, metadata, and, as available, their trailers the specifications for which are detailed in Schedule B. |

1.13 | “Subscription Video-On-Demand” or “SVOD” means the encrypted electronic or other non-tangible exhibition of a program or programs on a program service pursuant to which a consumer may elect to view programming at a time of the consumer’s choosing and for which no “per-transaction” or “per-exhibition” charge is made and such consumer as a condition of receiving and/or viewing any particular program, provided that a periodic premium subscription fee (on no less than a monthly basis) must be charged to the authorized representative for the privilege of viewing such exhibition and ====== 1-242 ====== |

1.14 | “Start Date” means the date a Title is first available for distribution on the Licensee Service as set forth on Schedule A. |

1.15 | “Titles” shall mean those motion pictures, television and other digital entertainment products listed on Schedule A, as such list may be updated from time to time by mutual written agreement of both parties. The foregoing notwithstanding, Distributor may, with Licensee’s consent, not to be unreasonably withheld, by written notice to Licensee substitute for any Title during the period prior to the commencement of its License Period, a comparable motion picture, television or other digital entertainment product. |

1.16 | “Title License Period” shall mean the period beginning upon the Start Date and ending as of the End Date set forth for each Title on Schedule A. |

1.17 | “Wireless Transmission” means delivery by means of wireless digital networks for commercial mobile radio services integrated through the use of any protocol now known or hereafter in existence, including, without limitation, the Wireless Application Protocol, Wi-Fi (e.g., 802.11(g)), Wi-Max, 2G, 3G, 4G, DVB-H, DMB, EV-DO, or any successor or similar digital technology for display on any viewing device (including, without limitation, personal digital assistants, mobile phones, pagers, or other Portable Devices) which is capable of wirelessly sending and/or receiving voice and/or audio and/or data and/or video communications. |

| 2. Grant of License and Delivery |

2.1 | In consideration for Licensee’s payment of the Minimum Guarantees and Running Fees for each Title and subject to the terms and conditions set forth herein, Distributor hereby grants to Licensee with respect to each Title a limited, non-assignable, nonexclusive license to distribute such Title by the Permitted Means to Authorized Users within the Territory during its Title License Period on an SVOD basis via the Licensee Service for receipt and viewing on Approved Devices and to distribute and utilize such promotional and advertising materials as Distributor may have available as to such Title and which Distributor determines may be appropriate for use by Licensee hereunder solely to promote the availability of ====== 1-243 ====== | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2.2 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2.3 | Licensee represents and warrants that as of the commencement of distribution of Titles on the Licensee Service, Licensee shall have put in place on such Licensee Service, and Licensee agrees that it will maintain on such Licensee Service throughout the Term, industry-standard encoding, encryption, DRM, digital and physical security systems and technologies (“Security Measures”) to prevent theft, pirating and unauthorized exhibition (including, without limitation, exhibition to unauthorized recipients and/or exhibition outside the Territory), and unauthorized copying of a Title or any part thereof and that such Security Measures shall be no less stringent or robust than the Security Measures that Licensee employs on such Licensee Service with respect to comparable programs distributed in comparable media that are licensed from any other distributor or provider of programming. Distributor shall have the right upon ten (10) days’ prior written notice, during regular business hours, at Distributor’s sole cost, to inspect and review Licensee’s delivery, security, and copy control/protection systems (including in any off-site facilities used by Licensee) from time to time as Distributor deems necessary, but in no event more than once during any calendar year. Licensee shall promptly notify Distributor if it ====== 1-247 ====== | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2.4 | The parties shall mutually agree upon the appropriate source for encoding, and Distributor shall deliver such mutually agreed-upon Source Material to Licensee. The Source Material will be of the same high quality and resolution of Source Material as is made available by Distributor to any third-party SVOD licensee in any format during the Title License Period. Examples of Source Material, which Licensee may request, are listed on Schedule B. Distributor shall loan to Licensee, at no cost, clones of such Source Material, which will be returned to Distributor. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2.5 | Licensee will, at its sole cost and expense, encode and create files of each Title from the Source Materials, from which streaming and downloaded exhibitions of such Title may be exhibited to Authorized Users via the Licensee Service. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2.6 | Without limiting any of the foregoing, Licensee agrees that each Title exhibited to Authorized Users shall, at Licensee’s expense, be secured from unauthorized distribution through an encryption or encoding technology that is in accordance with Section 2.3. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Term |

3.1 | This Agreement shall commence as of the Effective Date and end on the date ____ (_) years thereafter (“Term”). |

====== 1-248 ====== | |

3.2 | Except as otherwise provided herein, if either party is in default hereunder, the non-defaulting party may give notice of such default, and if the defaulting party does not cure such default within thirty (30) days after notice, the non-defaulting party may thereafter, in addition to all other remedies available, terminate this Agreement. For the avoidance of doubt, the cure period with respect to any Security Breach or Suspension Notice shall be as defined in Section 7.1. If Licensee terminates this Agreement due to a material default by Distributor, Distributor will refund or credit the unearned portion, if any, of the Minimum Guarantees back to Licensee within thirty (30) days of termination. Any of the following events shall be considered events of material default pursuant to the Agreement: (i) if Licensee fails to make payment of any amounts payable in accordance with the terms of the Agreement; (ii) if a party fails to duly perform or observe any material term, covenant or condition of the Agreement that such party is required to keep and perform (other than a payment obligation as set forth in clause (i) above); (iii) if a party shall be adjudicated a bankrupt or shall file a petition in bankruptcy or shall make an assignment for the benefit of creditors or shall take advantage of the provisions of any bankruptcy or debtor’s relief act; (iv) if an involuntary petition in bankruptcy is filed against a party and is not vacated or discharged within thirty (30) days; (v) if a receiver is appointed for a substantial portion of a party’s property and is not discharged within thirty (30) days; and/or (vi) if a party makes or attempts to make any assignment, transfer, or sublicense of this Agreement without the other party’s written consent, except as otherwise permitted hereunder. |

3.3 | Upon the expiration or earlier termination of this Agreement, all prospective rights and obligations of the parties under this Agreement will be extinguished, except for those rights and obligations that either by their express terms survive or are otherwise necessary for the enforcement of the Agreement. |

| 4. License Fees |

4.1 | Licensee shall pay to Distributor with respect to each Title a “License Fee” in the amount set forth with respect to such Title on Schedule A. | ||||||

====== 1-249 ====== | |||||||

4.2 | Timing of Payment

| ||||||

| 5. Reporting |

With respect to each calendar quarter during the Term, Licensee shall deliver to Distributor an electronic report (“Detail Report”) that sets out on a Title-by-Title basis the number of Views of each Title during such calendar month and in the aggregate for each prior calendar month during the Title License Period for such Title. Said Detail Reports shall pertain solely to the Titles and be no less detailed than that provided by Licensee to any of its other content providers for the Licensee Service and shall be provided to Distributor no later than _______ (___) days following the end of each such calendar quarter.

| 6. Withdrawal |

In addition to and not in derogation of its other rights pursuant to the Agreement, including without limitation pursuant to Section 7.1, Distributor shall have the right to withdraw any Title (a “Withdrawn Title”) from the Licensee Service at any time in Distributor’s sole discretion. Licensee will remove any Withdrawn Title within forty-eight (48) hours of receipt of a written or electronic notice to such effect from Distributor. Distributor shall, within thirty (30) days of such early withdrawal, refund to Licensee an amount (the “Refund”) equal to the product of: (i) the Refund Percentage set forth on Schedule D applicable to the portion of the Title License Period for such Title that has elapsed at the time of such withdrawal, multiplied by (ii) the License Fee for such Title. The foregoing notwithstanding, in the event such withdrawal is the result of a breach by Licensee of any of the terms of this Agreement, Distributor shall not be obligated to make a refund for such withdrawn Title to Licensee, whether pursuant to delivery of a Failure Notice or otherwise.

====== 1-250 ======

| 7. Suspension and Reinstatement |

7.1 | In the event that Licensee becomes aware of any circumvention or failure of Licensee’s secure storage, distribution, copy protection system, anti-piracy, or geofiltering technology that results or may result in the unauthorized availability of any Title, Licensee will provide notice to Distributor within twenty-four (24) hours describing in reasonable detail such circumvention or failure and Licensee’s response thereto (a “Failure Notice”). Licensee will provide continuing reports to Distributor regarding its response to the Security Breach until it is cured. |

7.2 | Upon delivery of a Failure Notice or otherwise, Distributor shall have the right immediately to suspend the availability of any or all Titles through the Licensee Service in the event and during the pendency of a Security Breach by notifying Licensee of such suspension (a “Suspension Notice”). “Security Breach” means a circumvention or failure of Licensee’s anti-piracy, DRM or geofiltering measures or other secure distribution system(s) or technology that results or may result in the unauthorized availability of any Title, which unauthorized availability may, in the sole judgment of Distributor, result in harm to Distributor or its business. Upon its receipt of a Suspension Notice, Licensee shall immediately remove the Title or make the Title inaccessible from the Licensee Service as soon as commercially feasible (but in no event more than twenty-four (24) hours after receipt of such Suspension Notice). If the cause of the Security Breach that gave rise to a Suspension Notice is corrected, repaired, solved or otherwise addressed to Distributor’s satisfaction, the period of suspension with respect to such Title(s) shall terminate upon written notice from Distributor and Licensee’s ability to distribute such Title shall resume immediately. In addition to and not in derogation of the foregoing or any other rights of Distributor under this Agreement, after three (3) such suspensions, Distributor shall have the right in its sole discretion to terminate this Agreement and withdraw all Titles from the Licensee Service; provided that subject to the final sentence of Section 6, if Distributor does so it will within thirty (30) days following such termination and withdrawal pay to Licensee a Refund (as defined in Section 6) for each Title so withdrawn. |

====== 1-251 ======

| 8. Representations and Warranties |

8.1 | Licensee represents and warrants that (i) it has full authority, capacity and ability to execute this Agreement and to perform all of its obligations hereunder, (ii) it shall at all times employ DRM and geofiltering technology in accordance with Section 2.3, and (iii) it shall not distribute the Titles other than as expressly permitted hereunder. Licensee will defend, indemnify and hold Distributor, its directors, officers and employees, harmless from any breach of the representations and warranties made herein. |

8.2 | Distributor represents and warrants that (i) it has full authority, capacity and ability to execute this Agreement and to perform all of its obligations hereunder (ii) it has all right, title and interest necessary to grant the license rights hereunder and, other than with respect to non-dramatic music performance rights, that Licensee’s distribution as contemplated hereunder shall not violate or infringe any rights of other parties, including any third-party providers of content contained in any Title hereunder, (iii) there are no encumbrances against or any claims, actions, suits or other proceedings pending or, to the best of Distributor’s knowledge, threatened with respect to any Titles hereunder that would interfere with Licensee’s distribution thereof, and (iv) the Titles hereunder will not when exhibited in accordance with the terms and conditions of this Agreement violate any applicable law, rule or regulation. Distributor will defend, indemnify and hold Licensee, its directors, officers and employees, harmless from any breach of the representations and warranties made herein. |

8.3 | Distributor represents that the Titles delivered hereunder shall be of good quality, reasonably free of defects and otherwise fit for the particular purpose intended hereunder. Distributor shall, without undue delay and at its cost and expense, replace any defective product and deliver such replacement to Licensee. |

| 9. Confidentiality |

Each party agrees that it shall not disclose to any third party (except for third-party income participants, only to the extent necessary and provided such parties are bound to a confidentiality agreement with substantially the same terms as provided herein) other than to fulfill its obligations under this Agreement the terms of this Agreement which are

====== 1-252 ======

| 10. General Provisions |

10.1 | The laws of the State of California will govern this Agreement, without reference to its choice of law rules. All disputes arising under this Agreement which cannot be resolved informally will be submitted for binding arbitration before a single arbitrator (who shall have experience in the entertainment industry) in Los Angeles, California pursuant to the Commercial Arbitration Rules of the American Arbitration Association; provided that neither party shall be precluded from seeking equitable relief to protect or enforce its rights hereunder during the pendency of such an arbitration. The award of the arbitrator will be final and binding and may be entered for judgment in any court of competent jurisdiction in Los Angeles County. Any dispute or portion thereof, or any claim for a particular form of relief (not otherwise precluded by any other provision of this Agreement), that may not be arbitrated pursuant to applicable state or federal law may be heard only in a court of competent jurisdiction in Los Angeles County. |

10.2 | This Agreement sets forth the entire agreement and understanding of the parties with respect to the subject matter hereof and cannot be amended except by a writing signed by each party. |

10.3 | Notwithstanding anything else herein, Licensee shall only distribute the Titles as expressly provided herein. |

10.4 | Licensee shall be solely responsible for any and all third-party clearances and payments, including without limitation music performance, if any, in connection with its distribution of the Titles. |

10.5 | Licensee shall not cut, edit, alter, or otherwise modify the Titles or the Source Material, or authorize any of the same, without Distributor’s prior written consent. In no event shall Licensee remove, cut, edit, alter, or otherwise modify any credits, copyright notices, or ====== 1-253 ====== |

10.6 | No waiver of any provision of this Agreement shall constitute a continuing waiver, and no waiver shall be effective unless made in a signed writing. |

10.7 | Notices and other communications required or permitted to be given hereunder shall be given in writing and delivered in person, sent via certified mail, or delivered by nationally-recognized courier service, properly addressed and stamped with the required postage, to the person signing this Agreement on behalf of the applicable party at its address specified below (and, in the case of Distributor, with a courtesy copy to at , Attn: _______) and shall be deemed effective upon receipt. Either party may from time to time change the person to receive notices or its address by giving the other party written notice of the change. |

10.8 | Neither party may assign this Agreement or its rights or obligations hereunder without the other party’s prior written consent, which shall not be unreasonably withheld. Notwithstanding the foregoing, the parties may assign this Agreement without obtaining the consent of the other party to any affiliated entity or in connection with any merger, consolidation, reorganization, sale of all or substantially all of its assets, or similar transaction. |

10.9 | At no time in the past, present, or future shall the relationship between Distributor and Licensee be deemed or intended to constitute an agency, partnership, joint venture, or a collaboration for the purpose of sharing any profits or ownership in common. Neither party shall have the right, power, or authority at any time to act on behalf of or to represent the other party, but each party hereto shall be separately and entirely liable for its own debts in all aspects. |

====== 1-254 ====== | |

10.10 | All representations and warranties of the parties made pursuant to the Agreement, and Sections 8, 9 and 10 of this Agreement, shall survive the termination or expiration of this Agreement. |

10.11 | The parties acknowledge and agree that the Titles are unique and irreplaceable properties and that the unauthorized exhibition or exploitation of such Titles will result in substantial and irreparable harm to Distributor and its business and operations that is not readily quantifiable, as it may affect the value of the Titles and the ability of Distributor to protect its rights in such Titles or to license such rights to others. Accordingly, Licensee agrees that money damages would not adequately compensate Distributor for the unauthorized exhibition or exploitation of the Titles. Licensee agrees that Distributor shall be entitled to an injunction (both preliminary and permanent) precluding any such unauthorized exhibition or exploitation. This right to an injunction shall be cumulative and not exclusive of any other rights, remedies, powers or privileges provided by law or this Agreement. |

10.12 | Distributor will have the unilateral right to suspend this Agreement upon written notice to Licensee in the event that any law or regulation adversely affecting the material terms and conditions of this Agreement, now or in the future, modifies or limits the use of DRM, copy protection or other security measures such that Licensee cannot legally implement or substantially comply with the terms of Section 2.3 or Section 7 of this Agreement or implement alternative and substantially comparable security or copyprotection measures to those so affected to the satisfaction of Distributor, such satisfaction not to be unreasonably or discriminatorily conditioned or withheld, which suspension will be effective upon receipt of such notice. If Licensee cannot implement alternative and substantially comparable security or copy-protection measures to those so affected within thirty (30) days of such notice, Distributor will have the right to terminate this Agreement upon providing Licensee written notice to that effect, such termination effective upon receipt of such notice. |

10.13 | No remedy conferred on either Party by any of the specific provisions of this Agreement is intended to be exclusive of any other remedy which is otherwise available to either party at law, in equity, by statute or otherwise, and except as otherwise expressly ====== 1-255 ====== |

10.14 | If Licensee shall be prevented from offering Titles by means of the Licensee Service, or if Distributor shall be prevented from delivering any Titles, by reason of an event of force majeure, the affected party shall attempt to eliminate the force majeure contingency and such performance shall be excused to the extent that it is prevented by reason of such an event of force majeure. For purposes of this Agreement, an “event of force majeure” in respect of a party shall mean, to the extent beyond the control of such party, any governmental action, nationalization, expropriation, confiscation, seizure, allocation, embargo, prohibition of import or export of goods or products, regulation, order or restriction (whether foreign, federal or state), war (whether or not declared), civil commotion, disobedience or unrest, insurrection, public strike, riot or revolution, lack of or shortage of, or inability to obtain, any labor, machinery, materials, fuel, supplies or equipment from normal sources of supply, strike, work stoppage or slowdown, lockout, or other labor dispute, fire, flood, drought, other natural calamity, damage or destruction to plant and/or equipment, or any other accident, condition, cause, contingency or circumstance (including, without limitation, acts of God) beyond the control of such party. An event of force majeure does not, however, include any party’s financial inability to make any of the payments required to be made under this Agreement, nor shall any event of force majeure relieve Licensee from the obligation to make any payments under this Agreement, provided the Titles are delivered to Licensee. |

10.15 | As between Distributor and Licensee, Licensee will be responsible for determining, collecting, and remitting all taxes that are required by law to be determined, collected and remitted with respect to the distribution of the Titles to Authorized Users. |

10.16 | The division of this Agreement into separate sections, subsections and/or exhibits and the insertion of titles or headings is for convenience of reference only and shall not affect the construction or interpretation of this Agreement. |

====== 1-256 ====== | |

10.17 | This Agreement may be executed in one or more counterparts, each of which shall be deemed an original and which together shall constitute one document. |

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, the parties have caused this Agreement to be executed by their duly authorized representatives as of the date first written above.

====== 1-257 ======

SCHEDULE A

Titles

Title | Start Date | End Date | Length of License | License Fee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

====== 1-259 ======

SCHEDULE B

Source Material Requirements and Specifications

====== 1-261 ======

SCHEDULE C

Security Specifications

====== 1-263 ======

SCHEDULE D

License Fee Refund Percentage

====== 1-265 ======

2012 WL 2317364

Only the Westlaw citation is currently

available.

United States District Court,

C.D. California.

Alexandre SINIOUGUINE

v.

MEDIACHASE LTD., et al.

No. CV 11–6113–JFW (AGRx). | June 11, 2012.

Attorneys and Law Firms

Michael D. Anderson, Anderson and Associates, Pasadena, CA, for Plaintiff.

Shari Mulrooney Wollman, Mark S. Lee, Don Brown, Adrianne E. Marshack, Manatt Phelps and Phillips LLP, Los Angeles, CA, for Defendant.

Opinion

ORDER GRANTING MEDIACHASE, LTD., CHRIS LUTZ AND JULIE MAGBOJOS’MOTION FOR: (1) SUMMARY JUDGMENT ON PLAINTIFF’S COMPLAINT AND COUNTERCLAIMS; MEDIACHASE’SDECLARATORY RELIEF CLAIMS; AND (2)PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT ONMEDIACHASE’S COPYRIGHTINFRINGEMENT COUNTERCLAIMS [filed 4/23/12; Docket No. 77]

Honorable JOHN F. WALTER, District Judge.

*1 On April 23, 2012, Defendants Christ Lutz (“Lutz”), Julie Magbojos (“Magbojos”), and Mediachase, Ltd. (“Mediachase”) (collectively, “Defendants”) filed a Motion for: (1) Summary Judgment on Plaintiff’s Complaint and Counterclaims; Mediachase’s Declaratory Relief Claims; and (2) Partial Summary Judgment on Mediachase’s Copyright Infringement Counterclaims (“Motion”). On April 30, 2012, Plaintiff Alexandre Siniouguine (“Siniouguine”) filed his Opposition. On May 7, 2012, Defendants filed a Reply. On May 25, 2012, Siniouguine filed his Sur–Reply pursuant to the Court’s May 18, 2012 Order. On June 1, 2012, Defendants filed their Response to Siniouguine’s Sur–Reply.

Pursuant to Rule 78 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Local Rule 7–15, the Court found the matter appropriate for submission on the papers without oral argument. The matter was, therefore, removed from the Court’s June 11, 2012 hearing calendar and the parties were given advance notice. After considering the moving, opposing, and reply papers, and the arguments therein, the Court rules as follows:

| I. Factual and Procedural Background1 |

Mediachase develops computer software used by businesses and provides consulting work related to its software. Mediachase was founded as a “startup” by Lutz and his brother and sister in 1997. Currently, Lutz is Mediachase’s Senior Vice President of Professional Services, and Magbojos, who has worked at Mediachase since 2000, is its President. Siniouguine is a Russian national who was hired by Mediachase to work as an “application developer” in 1999 pursuant to the Mediachase, Ltd Deal Memo (the “1999 Agreement”).2 The 1999 Agreement was signed by Siniouguine and Mediachase’s then-Treasurer, Melanie Lutz, who is Lutz’s sister. The 1999 Agreement provides for an “at will” employment relationship between Siniouguine and Mediachase, and Siniouguine has worked continuously for Mediachase pursuant to the 1999 Agreement from 1999 until March 2011. In addition, the 1999 Agreement provides, in relevant part: Company [Mediachase] shall own all the results and proceeds of Artist’s [Siniouguine’s] services hereunder, and all materials produced thereby and/or suggested or furnished by Artist, of any kind and nature whatsoever (collectively, “Results”), and all rights therein (including without limitation, all copyrights and copyright renewals and extensions), as a “work-made-for-hire” specially ordered or commissioned by Company, in perpetuity throughout the universe. If under applicable law the foregoing is not effective to place authorship and ownership of the Results and all rights therein in Company, then to the fullest extent allowed and for the full ====== 1-266 ====== *2 During his employment with Mediachase, Siniouguine received compensation and other benefits every month from the beginning of his employment in 1999 until he left the company in 2011, though the amount and nature of that compensation and those benefits varied according to the financial condition of Mediachase. Siniouguine’s compensation included a salary; payment of rent for an apartment in Los Angeles; payment of medical and/or dental insurance benefits; and payment for a cell phone. During the entire time Siniouguine was employed by Mediachase, he received at least one of the above forms of compensation, and, with the exception of a few months, Siniouguine received at least two if not all four forms of compensation. In addition, Siniouguine’s business related expenses were reimbursed directly by Mediachase during this period. During Siniouguine’s employment, Mediachase also provided him with the equipment and facilities required to perform his work, including a laptop computer, development software, miscellaneous software, and an office.3 Siniouguine occasionally worked from home, but when he did work from home he was required to log into Mediachase’s server so that Mediachase could track and coordinate his programming efforts with those of other Mediachase employees who were working on the same programs. Siniouguine was also required to use Mediachase’s project management collaboration software so that other members of the development team could track his progress. Mediachase also hired and paid for all persons who assisted Siniouguine in completing his work assignments. |

*3 On July 25, 2011, Siniouguine filed his Complaint against Defendants, alleging copyright infringement of the ECF Program, an accounting based on the alleged copyright infringement of the ECF program, and a declaration of copyright ownership of the ECF program. On September 19, 2011, Defendants filed their Answer to Siniouguine’s Complaint, and Mediachase filed its Counterclaim against Siniouguine and Virtosoftware, seeking a declaration that Mediachase was the copyright owner of the ECF program, seeking to invalidate Siniouguine’s copyright application for the ECF program, and ====== 1-267 ====== On November 3, 2011, Siniouguine and Virtosoftware filed their Answer to Mediachase’s Counterclaim, and Siniouguine filed a new Counterclaim against Mediachase alleging the identical copyright infringement, accounting, and declaratory relief claims only now relating to the Calendar.NET program. On November 28, 2012, Mediachase filed its Answer to Siniouguine’s Counterclaim and its Supplemental Counterclaim, seeking a declaration that Siniouguine does not own the copyright in the Calendar.NET program, seeking to invalidate Siniouguine’s copyright application for the Calendar.NET program, and alleging a claim for breach of contract. In their Motion, Defendants argue that the undisputed facts establish that Mediachase, and not Siniouguine, owns the copyrights in and to the Programs either by assignment or by application of the “work made for hire” doctrine or both, and that judgment should be entered in favor of Mediachase on each of Siniouguine’s claims asserted in the Complaint and Siniouguine’s Counterclaim; on Mediachase’s declaratory relief claims alleged in Mediachase’s Counterclaim and in Mediachase’s Supplemental Counterclaim; and the Court should enter partial summary judgment establishing Mediachase’s ownership of the Programs on all remaining claims and defenses, including Mediachase’s claim for copyright infringement, in which ownership of the copyrights in the Programs is an element. |

| II. Legal Standard |

Summary judgment is proper where “the movant shows that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.” Fed.R.Civ.P. 56(a). The moving party has the burden of demonstrating the absence of a genuine issue of fact for trial. SeeAnderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 256, 106 S.Ct. 2505, 91 L.Ed.2d 202 (1986). Once the moving party meets its burden, a party opposing a properly made and supported motion for summary judgment may not rest upon mere denials but must set out specific facts showing a genuine issue for trial. Id. at 250; Fed.R.Civ.P. 56(c), (e); see also Taylor v. List, 880 F.2d 1040, 1045 (9th Cir.1989) (“A summary judgment motion cannot be defeated by relying solely on conclusory allegations unsupported by factual data.”). In particular, when the non-moving party bears the burden of proving an element essential to its case, that party must make a showing sufficient to establish a genuine issue of material fact with respect to the existence of that element or be subject to summary judgment. See Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 322, 106 S.Ct. 2548, 91 L.Ed.2d 265 (1986). “An issue of fact is not enough to defeat summary judgment; there must be a genuine issue of material fact, a dispute capable of affecting the outcome of the case.” AmericanInternational Group, Inc. v. AmericanInternational Bank, 926 F.2d 829, 833 (9th Cir.1991) (Kozinski, dissenting).

*4 An issue is genuine if evidence is produced that would allow a rational trier of fact to reach a verdict in favor of the non-moving party. Anderson, 477 U.S. at 248. “This requires evidence, not speculation.” Meade v. Cedarapids, Inc., 164 F.3d 1218, 1225 (9th Cir.1999). The Court must assume the truth of direct evidence set forth by the opposing party. SeeHanon v. Dataproducts Corp., 976 F.2d 497, 507 (9th Cir.1992). However, where circumstantial evidence is presented, the Court may consider the plausibility and reasonableness of inferences arising therefrom. See Anderson, 477 U.S. at 249– 50; TW Elec. Serv., Inc. v. Pacific Elec.Contractors Ass’n, 809 F.2d 626, 631–32 (9th Cir.1987). Although the party opposing summary judgment is entitled to the benefit of all reasonable inferences, “inferences cannot be drawn from thin air; they must be based on evidence which, if believed, would be sufficient to support a judgment for the nonmoving party.” American InternationalGroup, 926 F.2d at 836–37. In that regard, “a mere ‘scintilla’ of evidence will not be sufficient to defeat a properly supported motion for summary judgment; rather, the nonmoving party must introduce some ‘significant probative evidence tending to support the complaint.’” Summers v. Teichert & Son, Inc., 127 F.3d 1150, 1152 (9th Cir.1997).

| III. Discussion |