====== 2-269 ======

Barry P. BarbashWillkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Copyright © 2017 by Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP. All rights reserved. These materials may not be reproduced or disseminated in any form without the express permission of Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP. The information included in this Summary Chart is current as of December 31, 2016. The author appreciates the efforts of Charles F. Gyer, an associate in Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP’s office in the District of Columbia, in the preparation of this Chart. Mr. Gyer has yet to be admitted to the Washington D.C. Bar and is practicing under the supervision of members of Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP who are current members of that Bar. If you find this article helpful, you can learn more about the subject by going to www.pli.edu to view the on demand program or segment for which it was written. |

====== 2-271 ======

RECENT TRENDS IN SEC INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS:

A SUMMARY CHART

Investment Management Institute 2017

Practising Law Institute

New York Conference Center

1177 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10036

March 23-24, 2017

Barry P. Barbash

Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP

787 Seventh Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10019-6099

BBarbash@willkie.com

====== 2-272 ======

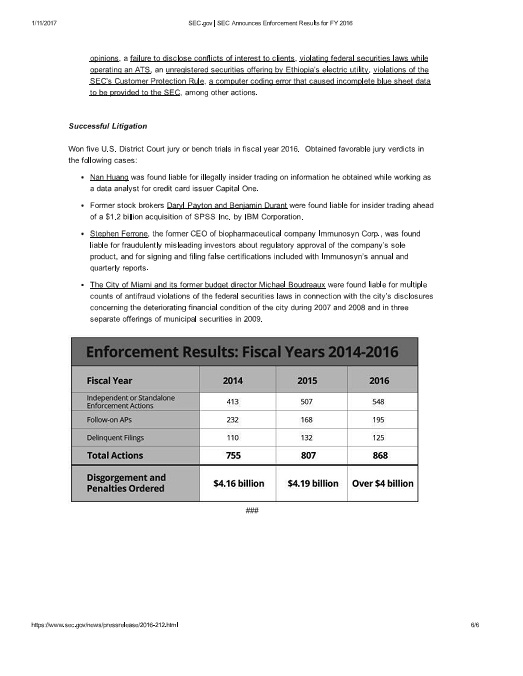

INTRODUCTION

The Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC” or “Commission”) continues to take an aggressive enforcement stance with respect to the asset management industry, filing 807 enforcement actions in 2015 and 868 enforcement actions in 2016 against investment advisers and investment companies over the last two years. These actions targeted diverse areas including: investment advisers’ compliance programs; investment advisers’ fiduciary duties; alleged misappropriation of client assets, misallocation of expenses, fraudulent investment performance track records, misvalued portfolio assets, violations of cybersecurity requirements, non-disclosure of conflicts of interest; violations of best execution obligations; and engaging in other activities deemed by the SEC to be fraudulent within the meaning of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The Commission, in what seems to be an ever increasing number of these actions, appears to have focused on obtaining acknowledgements of wrongdoing by individuals as part of settlement agreements. In a 2016 speech, the SEC’s Chair acknowledged the priority the Commission has placed on establishing individual liability.

The Summary Chart below covers recent SEC administrative actions and certain court cases involving asset management firms and associated individuals. The Chart, which is current as of December 31, 2016, sets out selected actions in reverse chronological order and covers the period beginning on January 1, 2015. Actions of particular significance because of their subject matter are highlighted in shaded text.

Set out as appendices to provide context with respect to the Chart are relatively recent statements of: the SEC; the Chair of the SEC; and current high ranking SEC staff members. Taken together, the statements indicate the current examination and enforcement themes of the SEC and its priorities in the asset management area.

The following abbreviations for statutes are used throughout the Summary Chart:

====== 2-275 ======

Recent Enforcement Actions Summary Chart | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Date Filed | Type of Action | Summary of Allegations | Charges | Settlement/Relief Sought |

12/14/16 | Alleged Failure by Private Equity Fund Manager to Obtain Advisory Board Consent for Co-Investments Presenting Conflicts of Interest | In New Silk Route Advisors, L.P., Advisers Act Release No. 4,587 (Dec. 14, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against New Silk Route Advisors, L.P. (“NSR”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, for allegedly failing to obtain advisory board consent for certain co-investments made by two private equity funds managed by NSR (the “NSR Funds”), as required by each NSR Fund’s limited partnership agreement. According to the SEC, each NSR Fund’s limited partnership agreement required NSR to obtain the consent of the Fund’s advisory board before making any investments in portfolio companies in which NSR or its affiliates were also investing or had invested. The SEC alleged that NSR’s co-founder and chief executive officer was a co-founder and chief executive officer of a separate Advisers Act-registered investment adviser, which managed other private equity funds (each, an “NSR Affiliate Fund”). According to the SEC, from approximately 2008 to 2014, NSR caused the NSR Funds to invest over $250 million in four portfolio companies in which an NSR Affiliate Fund also invested. The SEC alleged that these co-investments posed a conflict of interest for NSR, as NSR’s chief executive officer also owed fiduciary duties to each NSR Affiliate Fund. | The SEC alleged that NSR willfully violated Sections 206(2) and 206(4) of, and Rules 206(4)-7 and 206(4)-8 under, the Advisers Act. | NSR agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, to censure, and to pay a civil money penalty of $275,000. |

====== 2-276 ====== | ||||

The SEC asserted that NSR negligently failed to obtain the required advisory board consent for each NSR Fund’s co-investments with the NSR Affiliate Fund. The SEC alleged that NSR also failed to disclose, until May 2014, that it caused the NSR Funds to fund approximately $1.3 million in capital installments that were originally committed to one of the portfolio companies by the NSR Affiliated Fund, after the NSR Affiliated Fund exhausted its capital. According to the SEC, NSR failed to adopt policies and procedures reasonably designed to prevent violations of the Advisers Act arising from making co-investments with an affiliate without client consent as required by each NSR Fund’s limited partnership agreement. | ||||

12/12/16 | Alleged Material Misstatements and Omissions of Material Fact by Bank Custodian in Connection with Foreign Exchange Rate Pricing | In State Street Bank and Trust Company, 1940 Act Release No. 32,390 (Dec. 12, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against State Street Bank and Trust Company (“SSBTC”), which serves as custodian for investment companies registered under the 1940 Act, for allegedly making materially misleading statements and omissions in connection with SSBTC’s methodology of pricing certain foreign currency exchange transactions. According to the SEC, SSBTC offered a service under which SSBTC automatically processed and executed custody client purchases and sales of foreign currencies without requiring clients to negotiate prices on a trade- | The SEC alleged that SSBTC willfully violated Section 34(b) of the 1940 Act. The SEC alleged that SSBTC caused certain of its registered investment company clients to violate Section 31(a) of, and Rule | SSBTC agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, to pay disgorgement of $75,000,000, prejudgment interest of $17,369,416.51, and a civil money penalty of $75,000,000. |

====== 2-277 ====== | ||||

Alleged Failure to Maintain Accurate Transaction Records | by-trade basis (“Non-Negotiated Transactions”). The SEC alleged that SSBTC represented to its custody clients that, with respect to Non-Negotiated Transactions, it provided “best execution,” guaranteed the most competitive rates available, priced transactions at prevailing interbank or market rates, and that rates were based on, among other things, the size of the trade and SSBTC’s inventory of the currency. According to the SEC, SSBTC failed to disclose that it priced most Non-Negotiated Transactions at the applicable interbank market rate near the end of each trading day, regardless of when trade orders were received, after which SSBTC would then apply a predetermined, uniform markup (for purchases) or markdown (for sales), limited only to fall within the highest and lowest interbank rates of the day. The SEC alleged that, as a result of these practices, SSBTC often executed Non-Negotiated Transactions with custody clients at or near the highest and lowest rates in the interbank market between the time the market opened in the morning and the time that SSBTC priced the transactions. According to the SEC, SSBTC provided certain registered investment company clients with daily records of all transactions, as well as periodic transaction reports. The SEC alleged that these records and reports routinely contained the dates of Non-Negotiated Transactions and the prices at which SSBTC executed the transactions, but were materially misleading in light of SSBTC’s misstatements about | 3la-1(b) under, the 1940 Act. | ||

====== 2-278 ====== | ||||

how it priced Non-Negotiated Transactions, as the reports and records omitted information about the time of day at which trades were executed and how the prices were determined. | ||||

12/1/16 | Alleged Improper Valuation of Securities by Investment Adviser to Exchange-Traded Funds Alleged Failure to Adopt and Implement Policies and Procedures Reasonably Designed to Prevent Improper Valuation of Securities | In Pacific Investment Management Company LLC, Advisers Act Release No. 4,577 (Dec. 1, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Pacific Investment Management Company LLC (“PIMCO”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, for alleged improper valuation of certain positions held by an actively managed exchange-traded fund. The SEC alleged that PIMCO, in its management of the ETF, utilized an “odd lot strategy,” which involved purchasing relatively small blocks of securities, termed “odd lot” positions, that traded at a discount to larger institutional blocks of the same securities, termed “round lot” positions. According to the SEC, PIMCO would purchase odd lot positions of certain securities at a discount, and then value these positions at the higher round lot prices. The SEC alleged that, as a result of the odd lot strategy, PIMCO caused the ETF to overstate its net asset value. According to the SEC, the ETF regularly recorded performance increases reflected by the difference between the purchase price for an odd lot position and the higher round lot price used to value the position held | The SEC alleged that PIMCO willfully violated Sections 206(2) and 206(4) of, and Rules 206(4)-7 and 206(4)-8 under, the Advisers Act, and willfully violated Section 34(b) of, and Rule 22c-1 under, the 1940 Act. | PIMCO agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, to censure, to pay disgorgement of $1,331,628.74, prejudgment interest of $198,179.04, and a civil money penalty of $18,300,000. PIMCO also agreed to certain undertakings, including retaining an independent compliance consultant and adopting that compliance consultant’s recommendations. |

====== 2-279 ====== | ||||

by the ETF. The SEC alleged that PIMCO did not have a reasonable basis to believe that the round lot price accurately reflected the exit price the ETF would receive for those positions and therefore did not accurately value certain odd lot positions it purchased for the ETF. According to the SEC, PIMCO did not perform any contemporaneous analyses to determine whether the use of round lot prices for the ETF’s odd lot positions appropriately reflected fair value. The SEC alleged further that PIMCO’s pricing policy was not reasonably designed to ensure that odd lots purchased for the ETF were accurately priced and that the ETF’s net asset value was accurately calculated. According to the SEC, PIMCO’s pricing policies and procedures inappropriately relied on PIMCO’s traders to determine when to report position prices that did not reasonably reflect market value, without providing sufficient oversight of the traders’ determinations or any guidance regarding when to elevate significant pricing issues to PIMCO’s pricing committee or the valuation committee of the ETF’s Board of Trustees. The SEC asserted that PIMCO made materially misleading statements to the ETF’s Board of Trustees, as well as certain investors, by failing to disclose that the odd lot strategy was a significant source of the ETF’s performance. According to the SEC, PIMCO negligently provided monthly and annual disclosures that failed to disclose the effect of the odd lot strategy on the ETF’s performance and that the performance | ||||

====== 2-280 ====== | ||||

resulting from this strategy was not sustainable as the ETF grew in size. The SEC alleged that these disclosures implied that the ETF’s performance resulted from price appreciation in certain market sectors, while internal PIMCO reports indicated – and many of the drafters and reviewers of these disclosures understood – that a significant portion of the ETF’s favorable performance was attributable to initial gains from valuing odd lots at round lot prices. According to the SEC, PIMCO also failed to disclose the existence or effect of the odd lot strategy to the ETF’s Board of Trustees, which had specifically inquired about why the ETF outperformed PIMCO’s flagship mutual fund and its benchmark index. | ||||

11/21/16 | Auditor’s Alleged Failure to Comply with Professional Standards Auditor’s Alleged Cause of Advisers Act Violations | In Grassi & Co., CPAs, P.C, Advisers Act Release No. 4,572 (Nov. 21, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Grassi & Co., CPAs, P.C. (“Grassi”), a public accounting firm registered with the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, for allegedly failing to comply with professional standards in connection with audits of a private fund client, and for allegedly failing to detect investment adviser fraud. This case arises from the same set of facts discussed in Apex Fund Services (US), Inc., below. According to the SEC, Grassi served, from January 2012 until January 2013, as independent auditor for several private funds advised by ClearPath Wealth | The SEC alleged that Grassi caused ClearPath’s and ClearPath’s President’s violations of Sections 206(2) and 206(4) of, and Rule 206(4)-8 under, the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that Grassi engaged in | Grassi agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, to censure, to pay disgorgement of $130,000, prejudgment interest of $11,510.41, and a civil money penalty of $260,000, and to comply with certain undertakings, including engaging an independent |

====== 2-281 ====== | ||||

Management, LLC (“ClearPath”), an investment adviser registered by the State of Rhode Island. The SEC alleged that Grassi issued during this period nine audit reports, for years ended 2009 through 2011, containing unqualified opinions on the financial statements for four different funds advised by ClearPath. According to the SEC, from 2010 forward, ClearPath and ClearPath’s president were defrauding the funds they advised, and the investors in those funds, by misappropriating fund assets and making repeated misstatements to investors about the value and existence of fund investments. The SEC alleged that Grassi failed to detect evidence of the fraud by, among other things, neglecting to note the commingling of assets among multiple fund series when a restriction in each fund’s governing documents prohibited the assets and liabilities of each series from being commingled with that of any other series. According to the SEC, Grassi failed to make adjustments to financial statements it had provided earlier after its discovery of a previously undisclosed account for one of the funds that showed a $4.1 million margin loan had been taken against the fund’s assets. The SEC alleged that this conduct constituted a failure to detect fraud, thereby allowing the advisers to materially inflate the values of their investments without contradiction and to conceal use of limited partners’ investments for their own benefit. According to the SEC, as a result of Grassi’s failure to address ClearPath’s indications of fraud, five of Grassi’s nine audit reports were materially false, and those | improper professional conduct within the meaning of Section 4C(a)(2) of the Exchange Act and Rule 102(e)(1)(ii) of the Commission’s Rules of Practice. | compliance consultant to oversee compliance with all applicable securities laws. | ||

====== 2-282 ====== | ||||

reports enabled ClearPath and its principal to continue to report to limited partners materially inflated values of their investments without contradiction, to conceal use of limited partners’ investments for their own benefit, and continue their scheme to defraud the funds and their investors unimpeded. | ||||

11/10/16 | Alleged Affiliate Transactions by Unregistered Investment Adviser | In Derik J. Todd, Advisers Act Release No. 4,567 (Nov. 10, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings in connection with affiliate transactions allegedly conducted by Derik J. Todd, an unregistered investment adviser, and four limited liability companies, controlled, directly or indirectly, by Mr. Todd: Madison Capital Energy Income Fund II GP LLC (“Fund II GP”), Big Horn Minerals LLC (“Big Horn”), Madison Capital Investments LLC (“MCI”), and Madison Royalty Management LLC (“MRM”). According to the SEC, in 2010 Mr. Todd formed a private fund (“Fund II”) for the purpose of acquiring oil and gas royalty interests to generate a return for its investors. The SEC alleged that Fund II’s offering materials represented to investors, among other things, that Mr. Todd and Fund II’s general partner, Fund II GP, would use the assets and funds of Fund II for the “exclusive benefit” of Fund II, conduct transactions with affiliates on an “arms-length basis,” and that Mr. Todd, through MCI, would negotiate with sellers to purchase assets for Fund II at the “best price possible.” | The SEC alleged that Mr. Todd and Fund II GP willfully violated Section 17(a) of the Securities Act. The SEC alleged that Mr. Todd and Fund II GP willfully violated Section 10(b) of, and Rule 10b-5 under, the Exchange Act. The SEC alleged that Mr. Todd and Fund II GP willfully violated Sections 206(1) and 206(2) of the | Mr. Todd, Fund II GP, MCI, Big Horn, and MRM agreed to cease and desist from committing any violations of and any future violations of the charges, and to pay disgorgement of $205,673, prejudgment interest of $21,581, and a civil money penalty of $50,000. Mr. Todd agreed to be barred from association with, among others, any broker, dealer, investment adviser, or municipal adviser, and to be prohibited from serving as, among other |

====== 2-283 ====== | ||||

According to the SEC, Mr. Todd raised $11,125,500 from approximately 150 investors during Fund II’s offering period, October 2010 through January 2012. According to the SEC, from late 2011 through 2014, Mr. Todd and Fund II GP used their affiliates as intermediaries for many of Fund II’s sales and purchases of oil and gas royalty interests. The SEC alleged that Mr. Todd sold portions of Fund II’s assets to Big Horn and MRM at cost, and then sold those same interests to an independent third party at a profit. According to the SEC, Mr. Todd and Fund II GP enabled Mr. Todd to profit in the amount of $308,638 at the expense of Fund II and its investors through these affiliate transactions. The SEC asserted that, in taking these actions, Mr. Todd and Fund II GP acted inconsistently with the representations set out in Fund II’s offering materials regarding conducting transactions on an arms-length basis for the exclusive benefit of, and at the best price possible for, Fund II. | Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that MCI, Big Horn, and MRM willfully aided and abetted and caused Mr. Todd’s and Fund II GP’s violations of Section 17(a) of the Securities Act, Section 10(b) of, and Rule 10b-5 under, the Exchange Act, and Sections 206(1) and 206(2) of the Advisers Act. | things, an employee of any advisory board or investment adviser for five years. Fund II GP, MCI, Big Horn, and MRM agreed to censure. | ||

10/31/16 | Auditors’ Alleged Failure to Comply with Professional Standards in Connection With an Audit of a Venture Capital | In Adrian D. Beamish, CPA, Exchange Act Release No. 79,193 (Oct. 31, 2016), the SEC instituted public administrative proceedings against Adrian D. Beamish, CPA, an audit partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers (“PwC”), for allegedly failing to comply with professional standards in connection with his audits of a private venture capital fund. | The SEC alleged that Mr. Beamish engaged in improper professional conduct within the meaning of Section 4C of the | The SEC instituted proceedings to determine what, if any, remedial action should be taken, including whether Mr. Beamish should be censured, or denied, temporarily or |

====== 2-284 ====== | ||||

Fund | According to the SEC, PwC was retained in 2006 by a venture capital fund to conduct annual audits of its financial statements. The SEC alleged that Mr. Beamish served as the audit partner and was responsible for the planning, execution, and supervision of the audits, including the PwC audit team’s compliance with appropriate professional standards. According to the SEC, Mr. Beamish authorized PwC to issue audit reports on the fund’s financial statements with unqualified opinions for the year-end 2009 through year-end 2012 audits, even though the audits failed to comply with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (“GAAP”) and the audits failed to comply with Generally Accepted Accounting Standards (“GAAS”). The SEC in particular alleged that the fund’s investment adviser had improperly advanced management fees from the fund and that these advances were not properly accounted for or disclosed on the fund’s financial statements. According to the SEC, Mr. Beamish failed to meet GAAS standards by failing to seek the business rationale for why the advanced management fees balance increased each year between 2009 and 2011. The SEC alleged that, if the PwC audit team had investigated this increase, it would have discovered that the adviser had used these fees for the business operations of the fund’s affiliates and for the personal expenses of the adviser’s principal. According to the SEC, the fund’s financial statements violated GAAP by inconsistently and inaccurately | Exchange Act and Rule 102(e)(1)(ii) of the Commission’s Rules of Practice. | permanently, the privilege of appearing or practicing before the Commission as an accountant. | |

====== 2-285 ====== | ||||

disclosing the nature of the advanced management fees. The SEC alleged, for example, that the PwC audit team proposed a footnote that would have disclosed in the fund’s 2012 year-end financial statements that the amount advanced to the adviser exceeded all future expected management fees contractually owed to the adviser. According to the SEC, the fund’s adviser rejected this disclosure, and Mr. Beamish subsequently signed the fund’s unqualified opinion. https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2016/34-79193.pdf This action is related to a settlement discussed in greater detail below, Burrill Capital Management, LLC, Advisers Act Release No. 4,360 (Mar. 30, 2016), in which the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Burrill Capital Management, LLC, a now-defunct investment adviser, and certain of its principals, for allegedly misappropriating funds from a venture capital fund advisory client. | ||||

10/18/16 | Alleged Cross-Border Brokerage and Investment Advisory Services | In Bank Leumi le-Israel B.M., Advisers Act Release No. 4,555 (Oct. 18, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Bank Leumi le-Israel B.M. (“Leumi Israel”), an Israeli corporation, and two of its wholly-owned subsidiaries, Leumi Private Bank and Bank Leumi (Luxembourg) | The SEC alleged that Leumi violated Section 15(a) of the Exchange Act. | Leumi agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, to censure, to |

====== 2-286 ====== | ||||

S.A. (“Leumi Luxembourg” and, collectively with Bank Leumi and Leumi Private Bank, “Leumi”), for allegedly providing brokerage and investment advisory services to U.S. customers without registering as a broker-dealer under the Exchange Act and an investment adviser under the Advisers Act. According to the SEC, between at least 2002 through 2009, Leumi provided brokerage services to U.S. customers without registering as a broker-dealer with the Commission, and Leumi Private Bank provided investment advisory services to U.S. customers for compensation without registering as an Investment Adviser with the Commission. The SEC alleged that, during this period, at least 11 different representatives from Leumi traveled to the U.S. on 65 occasions to provide investment advice or solicit securities transactions at some 245 individual meetings. According to the SEC, Leumi became aware in at least 2008 that it faced the risk of violating federal securities laws by providing these services to U.S. customers without being registered as a broker-dealer and investment adviser. The SEC alleged that Leumi began to adopt policies and procedures designed to bring Leumi in compliance with federal securities laws, such as discontinuing travel by Leumi representatives to the U.S. in April 2009. Despite these policies, according to the SEC, from 2009 to 2013, Leumi continued to provide brokerage services to at least 711 separate customer accounts with securities holdings beneficially | The SEC alleged that Leumi Private Bank violated Section 203(a) of the Advisers Act. | pay disgorgement of $3,372,700, and a civil money penalty of $1,526,228. | ||

====== 2-287 ====== | ||||

owned by U.S. customers. The SEC alleged that, between 2002 and 2013, Leumi held securities in brokerage accounts for U.S. customers with an aggregate peak value of $537 million and generated a pre-tax income of $3.37 million from U.S. cross-border securities business. | ||||

10/18/16 | Alleged Improper Valuation of Illiquid Securities by Adviser to Open-End Fund | In Calvert Investment Management, Inc., Advisers Act Release No. 4,554 (Oct. 18, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Calvert Investment Management, Inc. (“Calvert”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, in connection with alleged improper fair valuation of certain illiquid securities held by mutual funds advised by Calvert. Calvert is a well-known investment adviser of, among other clients, investment companies registered under the 1940 Act. The SEC alleged that, between March 2008 and October 2011, certain of these investment companies held securities issued by Toll Road Investors Partnership II, L.P. (the “Toll Road Bonds”), which were illiquid securities and with respect to which only limited information was publicly available from which to value the securities. According to the SEC, during this time, Calvert’s calculation of the Toll Road Bonds’ fair value was | The SEC alleged that Calvert willfully violated Sections 206(2) and 206(4) of, and Rule 206(4)-8 under, the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that Calvert caused certain mutual funds advised by Calvert to violate Section 34(b) of, and Rules 22c-1 and 38 a-1 under, the 1940 Act. The SEC alleged that Calvert caused | Calvert agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, to censure, and to pay a civil money penalty of $3.9 million. Calvert also agreed to recalculate its valuation of the Toll Road Bonds for the relevant period, using a methodology approved by the SEC. |

====== 2-288 ====== | ||||

improper as Calvert failed to include certain data in making its calculations, including, among other things, the prices at which the investment companies traded the Toll Road Bonds, values assigned by other holders of the Toll Road Bonds, and other market data. The SEC alleged that Calvert instead relied primarily on a third-party analytical tool that did not properly account for the Toll Road Bonds’ future cash flows and, as a result, inflated Calvert’s fair value prices for the securities. According to the SEC, the inaccurate valuations of the Toll Road Bonds caused the investment companies to execute shareholder transactions at an incorrect net asset value and for Calvert to collect inflated asset-based fees. The SEC alleged that, during the relevant time period, certain shareholders redeemed fund shares at an overstated net asset value at the expense of the remaining shareholders. The SEC alleged that, in October 2011, Calvert discovered that its valuation of the Toll Road Bonds was inaccurate and made adjustments to its valuations that caused a markdown of each investment company’s net asset value. According to the SEC, in December 2011, Calvert sought to compensate the affected shareholders and investment companies for any losses resulting from its markdown of net asset value. The SEC alleged that the methodology used by Calvert to compensate affected shareholders was based on an insufficient process that was not based on full transactional data and was not consistent with Calvert’s own policies and procedures relating to net asset value correction. Over | a mutual fund advised by Calvert to violate Section 17(a) of the 1940 Act. | |||

====== 2-289 ====== | ||||

half of the SEC’s settlement order was an effective critique of the process used by Calvert to compensate shareholders. According to the SEC, Calvert’s compensation calculations were based on a netting out of subscription and redemption activity at the intermediary account level and did not include data concerning underlying shareholder activity in subaccounts held through certain intermediaries. The SEC alleged that this compensation methodology likely understated the effects of the improper valuation. The SEC separately alleged that, in July 2011, Calvert separately caused one of its investment company clients to engage in a prohibited transaction in violation of Section 17(a) of the 1940 Act. The SEC alleged that Calvert caused an investment company to purchase certain Toll Road Bonds from another investment company that Calvert sub-advised, and did not timely report this transaction to the first investment company’s board of trustees. | ||||

10/13/16 | Alleged Failure by a Registered Investment Adviser to Supervise a Research Analyst | In Artis Capital Management, L.P., Advisers Act Release No. 4,550 (Oct. 13, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Artis Capital Management, L.P. (“Artis”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act until it withdrew its registration in April 2016, and a former senior analyst at Artis, for allegedly failing to | The SEC alleged that Artis and Artis’s former senior analyst failed reasonably to supervise Mr. Teeple within the | Artis agreed to censure, and to pay disgorgement of $6,295,084 and a civil money penalty of $2,582,991. |

====== 2-290 ====== | ||||

Alleged Failure by a Registered Investment Adviser to Adopt and Implement Policies and Procedures to Detect and Prevent Insider Trading | detect insider trading by an Artis analyst. According to the SEC, in 2007 Artis hired Matthew Teeple as a research analyst to evaluate potential investments in certain types of technology companies. The SEC alleged that, unlike other research analysts at Artis, Mr. Teeple did not work out of Artis’s San Francisco office, did not construct analytical models regarding the companies he covered, did not provide written research reports, and did not maintain research files available for review by anyone at Artis. According to the SEC, Mr. Teeple instead worked exclusively out of his Southern California home and provided his recommendations, which were based exclusively on industry sources, to Artis by telephone. The SEC alleged that Artis’s policies and procedures relating to insider trading required any employee that believed he or she was in possession of material nonpublic information to immediately cease recommending any transaction in the security and to consult with Artis’s chief compliance officer. According to the SEC, even though Artis was aware that Mr. Teeple based his recommendations on industry sources, Artis did not take additional steps to ensure its insider trading policies and procedures were complied with, such as by requiring Mr. Teeple to log his interactions with employees of public companies. The SEC alleged further that, on at least two separate occasions in 2008, Mr. Teeple obtained material non- | meaning of Section 203(e)(6) of the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that Artis willfully violated Section 204A of the Advisers Act. | Artis’s former senior analyst agreed to pay a civil money penalty of $130,000, and to be suspended from association with, among others, any broker, dealer, or investment adviser for a period of one year. | |

====== 2-291 ====== | ||||

public information in connection with the impending acquisition of a technology company whose securities were publicly traded by another company. According to the SEC, Mr. Teeple made recommendations to a senior analyst at Artis based on this information, which resulted in profitable trades for Artis. The SEC alleged that Artis and its senior analyst should have been aware that these timely recommendations, which preceded a major public announcement by the company, may have been based on material non-public information in light of Mr. Teeple’s industry connections. A reasonable supervisor, according to the SEC, would have investigated whether Mr. Teeple had access to inside information to support these recommendations. The SEC alleged that Artis and its senior analyst failed to ask questions about the sources of the information and failed to inform Artis’s chief compliance officer of the possibility that the recommendations were made on inside information. This action is related to the civil proceeding SEC v. Teeple, et al, 13-cv-2010 (S.D.N.Y.), in which the SEC successfully sued Mr. Teeple for insider trading, and the criminal case U.S. v. Teeple, 13-cr-339 (S.D.N.Y.), in which Mr. Teeple pled guilty to one count of criminal conspiracy to commit securities fraud. | ||||

====== 2-292 ====== | ||||

10/4/16 | Alleged Materially False and Misleading Statements by a Registered Investment Adviser in Connection with Allocation of Trades | In Oracle Investment Research, Advisers Act Release No. 4,545 (Oct. 4, 2016), the SEC instituted public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Laurence Isaac Baiter, doing business as Oracle Investment Research (“Oracle”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act until it withdrew its registration in August 2013, for alleged breaches of its fiduciary duties in connection with the allocation of trades and false disclosures provided to advisory clients. According to the SEC, Oracle provided investment advisory services to separate accounts and to a registered investment company under the 1940 Act (the “Oracle Mutual Fund”). The SEC alleged that Oracle began, in May 2012, to execute a day-trading strategy in which it executed trades on behalf of itself in the same omnibus account as other separately managed account clients. According to the SEC, this strategy violated Oracle’s written policies and procedures, which required Oracle to provide clients with priority on all purchases and sales prior to the execution of proprietary accounts, and was also contrary to Oracle’s disclosures in its Form ADV Part 2A. The SEC alleged that Oracle’s practice of allocating trades after execution resulted in profitable trades being allocated to Oracle’s proprietary account while unprofitable trades were disproportionately allocated to client accounts. According to the SEC, Oracle’s misrepresentations and omissions constituted a breach of its fiduciary duty. The SEC alleged further that Oracle falsely represented | The SEC alleged that Oracle willfully violated Section 17(a) of the Securities Act, Section 10(b) of, and Rule 10b-5 under, the Exchange Act, and Sections 206(1), 206(2), 206(4), and 207 of, and Rule 206(4)-8 under, the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that Oracle willfully aided and abetted and caused the Oracle Mutual Fund’s violations of Section 13(a) of the 1940 Act. The SEC alleged that Oracle willfully violated, aided and abetted and caused the Oracle Mutual | The SEC instituted cease-and-desist proceedings to determine what, if any, remedial action, including, but not limited to, disgorgement, interest and civil penalties, is appropriate against Oracle. |

====== 2-293 ====== | ||||

to clients invested through separately managed accounts that they would not be charged additional management fees if their assets were invested in the Oracle Mutual Fund. According to the SEC, Oracle then manually deducted the Fund’s management fees from these accounts. The SEC alleged that the Oracle Mutual Fund’s statement of additional information disclosed to investors that the Fund was diversified, as defined in Section 5(b)(1) of the 1940 Act, and that the Fund would not invest 25% or more of the Fund’s net assets in securities of issuers in a single industry. According to the SEC, however, in numerous fiscal quarters Oracle caused the Oracle Mutual Fund to become non-diversified and/or to invest 25% or more of the Fund’s net assets in securities of issuers in a single industry. | Fund’s violations of Section 34(b) of the 1940 Act. | |||

9/29/16 | Alleged Use of Fund Assets by Advisers Act-Registered Investment Adviser to Pay Bribes to Foreign Government Officials in Violation of Foreign Corrupt | In Och-Ziff Capital Management Group LLC, Advisers Act Release No. 4,540 (Sept. 29, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Och-Ziff Capital Management Group LLC (“Och-Ziff”), an institutional alternative asset manager, OZ Management LP (“OZ”), a subsidiary of Och-Ziff and an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, Och-Ziff’s chief executive officer, and Och-Ziff’s chief financial officer, in connection with numerous transactions in which Och-Ziff allegedly paid bribes to high-ranking government officials in Africa. | The SEC alleged that Och-Ziff willfully violated Sections 30A, 13(b)(2)(A), and 13(b)(2)(B) of the Exchange Act. The SEC alleged that OZ violated Section 206(4) of, | Och-Ziff, OZ, Och-Ziff’s chief executive officer, and Och-Ziff’s chief financial officer agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges. |

====== 2-294 ====== | ||||

Practices Act | The SEC alleged that, from 2007 through 2011, Och-Ziff entered into a series of transactions and investments in which Och-Ziff paid bribes through intermediaries, agents and business partners to high-ranking government officials in several African countries, including Libya, Chad, Niger, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (“DRC”). According to the SEC, a majority of these bribes involved the use of Och-Ziff client assets managed by OZ, rather than Och-Ziff’s own capital, and were paid to foreign government officials to obtain or retain business for Och-Ziff and its business partners. The SEC alleged that, in 2007, the head of Och-Ziff’s European office secured an investment mandate from a Libyan sovereign wealth fund by funneling Och-Ziff client assets through a shell company established by a third-party intermediary, which then used the assets to pay bribes to Libyan government officials. According to the SEC, Och-Ziff authorized these transactions even though it was aware that doing business with the intermediary presented risks of violating anti-corruption laws, as the intermediary had connections to high-ranking government officials in Libya and business interests that were difficult to accurately discern. The SEC further alleged that, beginning in 2008, Och-Ziff entered into a partnership with an Israeli businessman (“DRC Partner”) with close ties to high-ranking government officials within the DRC. | and Rule 206(4)-8 under, the Advisers Act, and willfully violated Sections 206(1) and 206(2) of the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that Och-Ziff’s chief executive officer and Och-Ziff’s chief financial officer each caused Och-Ziff’s violations of Section 13(b)(2)(A) of the Exchange Act. The SEC alleged that Och-Ziff’s chief financial officer caused Och-Ziff’s violations of Section 13(b)(2)(B) of the Exchange Act. | Och-Ziff and OZ agreed to censure and to pay disgorgement of $199,045,167. Och-Ziff’s chief executive officer agreed to pay disgorgement of $2,173,718. | |

====== 2-295 ====== | ||||

According to the SEC, the purpose of this partnership was ostensibly for Och-Ziff to fund the DRC Partner’s mining-related interests while he used his government contacts to acquire assets and navigate the DRC business environment for his and Och-Ziff’s benefit. The SEC alleged, however, that the head of Och-Ziff’s European office and at least one other Och-Ziff employee were aware that the DRC Partner would use the funds Och-Ziff provided to him to pay bribes to government officials, acquire assets with the help of government benefactors at a significant discount to the value of the asset, and gain favor for his mining interests in the DRC. According to the SEC, Och-Ziff entered into several transactions, between 2008 and 2011, with certain entities controlled by the DRC Partner, including more than $250 million in loans, through which Och-Ziff client assets were used for payments to DRC government officials. The SEC alleged that Och-Ziff’s senior executives, including its chief executive officer and chief financial officer, reviewed due diligence regarding the DRC Partner, which revealed a history of suspicious transactions, allegations of illegal conduct, and close connections with high-ranking government officials in the DRC. According to the SEC, Och-Ziff’s chief executive officer, after reviewing this diligence, directed subordinates to continue moving forward with potential transactions with the DRC Partner. | ||||

====== 2-296 ====== | ||||

The SEC alleged separately that Och-Ziff caused client assets invested in an Africa-focused fund controlled by Och-Ziff to be used in self-dealing transactions to benefit an Och-Ziff employee, Och-Ziff’s business partners, and Och-Ziff itself. According to the SEC, an Och-Ziff employee caused the fund to make investments in a London-based mining holding company controlled by the third-party intermediary in Libya so that the intermediary could pay back an $18 million personal loan owed to the Och-Ziff employee. The SEC alleged that the Africa-focused fund’s assets were also used in 2011 to purchase shares of a London-based oil and gas company, and that this transaction was designed to provide $50 million to a business partner of Och-Ziff to further the partner’s and Och-Ziff’s interests in the Republic of Guinea. According to the SEC, OZ failed to disclose all material facts and conflicts of interest arising from these transactions in its communications with the fund’s investors. The SEC alleged that Och-Ziff failed to impose procedures or measures sufficient to prevent corruption or provide reasonable assurance that transaction documents appropriately reflected third-party use of funds. According to the SEC, Och-Ziff adopted in 2008 an anti-corruption policy and procedures, which applied to OZ and all of OZ’s affiliates, and required rigorous due diligence and anti-corruption measures designed to provide reasonable assurances that transactions would be executed in accordance with management’s authorization and accurately recorded. The SEC alleged that Och-Ziff failed to follow these procedures in connection with the | ||||

====== 2-297 ====== | ||||

transactions described above despite indications of substantial corruption risks. | ||||

9/23/16 | Alleged Prohibited Cross Trading by a Registered Investment Adviser Alleged Failure to Implement Compliance Policies and Procedures to Identify Impermissible Cross Trading | In Aviva Investors Americas, LLC, Advisers Act Release No. 4,534 (Sept. 23, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Aviva Investors Americas, LLC (“Aviva”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, in connection with allegedly inappropriate cross trades arranged by Aviva Investors North America, Inc. (“AINA”), an investment adviser that withdrew its registration under the Advisers Act in 2014 and was succeeded by Aviva, which assumed certain of AINA’s asset management functions. According to the SEC, between March 2010 and December 2011, three AINA traders arranged to sell fixed income securities from certain AINA advisory clients to counterparty broker-dealers and then repurchased the same securities the following day on behalf of different AINA advisory clients. The SEC alleged that AINA conducted these trades without obtaining an exemptive order as required by Sections 17(a)(1) and 17(a)(2) of the 1940 Act. According to the SEC, 161 of these trades were between registered investment company clients of AINA and their affiliates, which required an exemptive order from the Commission. | The SEC alleged that AINA caused certain of its advisory clients to violate Sections 17(a)(1) and 17(a)(2) of the 1940 Act. The SEC alleged that AINA violated Sections 206(3) and 206(4) of, and Rule 206(4)-7 under, the Advisers Act. | Aviva agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, and to pay a civil money penalty of $250,000. |

====== 2-298 ====== | ||||

The SEC further alleged that AINA’s compliance department failed to detect these trades even though the department had identified cross trading as a risk and took steps to identify and prevent impermissible cross trading. According to the SEC, the individuals working on cross trading within AINA’s compliance department were underqualified and lacked resources to effectively detect impermissible cross trading, even though senior members of the compliance department had made requests for additional resources to AINA senior management. | ||||

9/14/16 | Alleged Failure by a Private Equity Firm to Disclose Conflicts of Interest Related to Fees and Expenses | In First Reserve Management, L.P., Advisers Act Release No. 4,529 (Sept. 14, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against First Reserve Management, L.P. (“First Reserve”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, for allegedly failing to appropriately disclose conflicts of interest to its private equity fund clients. According to the SEC, in late 2013, First Reserve caused two of its private equity fund clients to collectively become 75% owners of First Reserve Momentum L.P. (“FRM”), an entity that was itself a pooled investment vehicle formed by First Reserve to invest in small oil field equipment and services companies. The SEC alleged that FRM had two subsidiaries that were formed by First Reserve to provide investment management services to FRM. | The SEC alleged that First Reserve violated Sections 206(2) and 206(4) of, and Rules 206(4)-7 and 206(4)-8 under, the Advisers Act. | First Reserve agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, and to pay a civil money penalty of $3.5 million. First Reserve also voluntarily reimbursed its private fund clients that were affected by these violations, including: $7,435,737 to two private funds in connection with the subsidiaries of FRM; |

====== 2-299 ====== | ||||

According to the SEC, First Reserve caused the private equity funds invested in FRM to pay a proportionate share of the subsidiary’s organizational and startup expenses. The SEC alleged that, between 2013 and 2015, over $7 million (approximately 15%) of the private equity funds’ capital contribution to FRM were used to pay the expenses of the subsidiaries, including the cost of each entity’s formation, and general operating costs such as rent, utilities, and salaries. According to the SEC, this structure allowed First Reserve to avoid incurring certain expenses in connection with providing investment advisory services to the funds, which created a conflict of interest that was not disclosed to the funds’ investors or advisory boards. The SEC alleged that First Reserve did not disclose to the funds prior to commitment of capital or prior to the expenses being incurred, that the funds’ capital commitment would be used to pay these expenses. The SEC asserted that First Reserve also inappropriately allocated insurance premium expenses to several of its private fund clients. The SEC alleged that the governing documents for these funds allowed insurance premium expenses to be borne by the funds for insurance that related to the affairs of the funds. According to the SEC, beginning in at least 2008, First Reserve allocated all of the premiums for an insurance policy that covered First Reserve for certain risks that did not pertain to its management of these funds. | $733,012 to various funds in connection with the allocation of insurance premiums; and $179,466 to various funds in connection with legal fee discounts. | |||

====== 2-300 ====== | ||||

The SEC further alleged that, between 2010 and 2014, First Reserve retained a law firm to provide services to First Reserve and its various funds. According to the SEC, First Reserve requested and obtained from the law firm a discount for legal services provided to First Reserve, even though the majority of work performed by the law firm was related to the funds. The SEC alleged that the funds did not receive a discount on the same kind of services that had been discounted for First Reserve, which created a conflict of interest that was not disclosed. According to the SEC, in 2013 First Reserve disclosed in its Form ADV the possibility that it could receive service provider discounts that could be more favorable than those of the funds, but at no time disclosed to the funds or its investors that it was receiving a discount for legal services. | ||||

9/8/16 | Alleged Failure to Track Additional Commission Costs Charged by Subadvisers Trading Outside of Wrap-Fee Program | In Raymond James & Associates, Inc., Advisers Act Release No. 4,525 (September 8, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Raymond James & Associates, Inc. (“Raymond James”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, for allegedly failing to appropriately disclose commission costs charged to clients invested in a wrap-fee program. According to the SEC, Raymond James offered advisory clients access to third-party managers through a wrap-fee program in which each client invested in the | The SEC alleged that Raymond James violated Section 206(4) of, and Rule 206(4)-7 under, the Advisers Act. | Raymond James agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, and to pay a civil money penalty of $600,000. |

====== 2-301 ====== | ||||

program would select a participating third-party manager to act as Raymond James’ subadviser. The SEC alleged that clients in the wrap-fee program were not charged for commissions on trades executed by Raymond James, but were charged for commissions on trades executed by all other broker-dealers. According to the SEC, Raymond James disclosed to clients that certain subadvisers participating in the program executed nearly all client trades with a broker-dealer other than Raymond James, but failed to disclose the amount of additional commission costs incurred by clients invested in the program. According to the SEC, the additional commission costs were instead embedded in the security price reported for each purchase or sale on periodic account statements that Raymond James provided to clients in the program. The SEC alleged that this practice meant that clients in the program were unable to take these costs into consideration when negotiating a wrap-fee with Raymond James. The SEC alleged further that Raymond James did not collect any information from the subadvisers regarding the amount of the embedded commission costs and failed to adopt and implement written policies and procedures to make this cost information available to clients invested in the wrap-fee program. In determining to accept Raymond James’ offer, the SEC considered remedial acts undertaken by Raymond James and cooperation afforded the SEC staff. In | ||||

====== 2-302 ====== | ||||

particular, Raymond James indicated that it would disclose on its periodic statements to clients whenever additional commissions may have been charged and also maintain a website that discloses the trading practices of subadvisers participating in the program. | ||||

9/8/16 | Alleged Failure to Track Additional Commission Costs Charged by Subadvisers Trading Outside of Wrap-Fee Program | In Robert W. Baird & Co. Incorporated, Advisers Act Release No. 4,526 (September 8, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Robert W. Baird & Co. Incorporated (“Robert Baird”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, for allegedly failing to appropriately disclose commission costs charged to clients invested in a wrap-fee program. The facts of this case are similar to the facts of the above case, Raymond James & Associates, Inc., Advisers Act Release No. 4,525 (September 8, 2016). The SEC alleged that Robert Baird, like Raymond James, failed to adopt and implement policies and procedures reasonably designed to track and disclose the trading practices of certain of the subadvisers participating in Robert Baird’s wrap-fee programs. | The SEC alleged that Robert Baird violated Section 206(4) of, and Rule 206(4)-7 under, the Advisers Act. | Robert Baird agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, and to pay a civil money penalty of $250,000. |

8/25/16 | Alleged Omissions of Material Fact in Application for Exemptive Relief | In Orinda Asset Management, LLC, Advisers Act Release No. 4,513 (August 25, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Orinda Asset Management, LLC (“Orinda”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, | The SEC alleged that Orinda willfully violated, and caused the funds’ sponsoring | Orinda agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the |

====== 2-303 ====== | ||||

Under the 1940 Act Alleged Failure to Disclose Side Agreement that Waived Adviser’s Ability to Terminate Subadviser | for allegedly omitting material facts in an application for exemptive relief and other disclosures filed with the Commission. According to the SEC, Orinda advised two 1940 Act-registered investment companies through a manager-of-managers structure, allocating assets of the investment companies among unaffiliated investment managers that served as subadvisers to the funds. The SEC alleged that Orinda engaged a lead subadviser to assist in managing the investment companies and select and monitor other subadvisers to the investment companies. According to the SEC, Orinda and the subadviser negotiated an agreement under which Orinda would pay the subadviser “termination payments” if Orinda were to terminate the subadviser for any reason other than “for cause.” Section 15(a) of, and Rule 18f-2 under, the 1940 Act require the approval of a registered investment company’s shareholders before retaining a subadviser or making any material changes to an existing subadvisory agreement. The SEC alleged that Orinda sought an order from the Commission exempting it from compliance with these shareholder approval obligations. Such an order is not unusual, and many such orders have been granted by the SEC. According to the SEC, after reviewing the application, the SEC’s Division of Investment Management communicated to Orinda and the investment companies’ board of directors that it would not support the application for an exemptive | administrators’ violations of, Section 34(b) of the 1940 Act. | charges, to censure, and to pay a civil money penalty of $75,000. | |

====== 2-304 ====== | ||||

order if the agreement providing for termination payments to the subadviser were included. The SEC alleged that Orinda then terminated this aspect of its agreement with the subadviser and informed the SEC of its action. According to the SEC, Orinda then reached a new agreement with the subadviser under which Orinda waived its right to terminate the subadviser for any reason. The SEC alleged further that Orinda then filed a new application for exemptive relief that did not disclose the new agreement. According to the SEC, the prospectus and statement of additional information filed with the Commission for each investment company failed to disclose the second agreement and falsely indicated that all of the subadvisory agreements could be terminated at any time by Orinda without penalty. The Orinda settlement is noteworthy as it reflects one of only a few instances over time in which the SEC commenced an enforcement case relating to non-compliance with a Commission exemptive order under the 1940 Act. | ||||

8/24/16 | Alleged Failure by a Private Equity Advisory Firm to Disclose Transaction Fee Allocation Methodology | In WL Ross & Co. LLC, Advisers Act Release No. 4,494 (August 24, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against WL Ross & Co. LLC (“WL Ross”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, for allegedly failing to appropriately disclose its method of allocating transaction fees received from portfolio companies owned by WL Ross’s private equity fund clients. | The SEC alleged that WL Ross violated Sections 206(2) and 206(4) of, and Rule 206(4)-8 under, the Advisers Act. | WL Ross agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, and to pay a civil money penalty of $2.3 million. |

====== 2-305 ====== | ||||

According to the SEC, WL Ross advised private equity funds under the terms of governing documents that permitted WL Ross to receive certain transaction fees from the portfolio companies owned by the funds including break-up, broken deal, and monitoring fees. The SEC alleged that the funds’ governing documents required that the transaction fees received by WL Ross would be offset with a corresponding reduction in the management fee charged to a fund by 50% or 80% of the amount of the transaction fee, depending on the fund. According to the SEC, WL Ross allocated a percentage of the transaction fees it received directly to the funds to offset the quarterly management fees it received. The SEC alleged that the governing documents of each fund were unclear as to how the transaction fees would be allocated when co-investors, which are not advised by WL Ross and therefore not subject to any offsetting provisions, invested in the same portfolio company. According to the SEC, WL Ross interpreted the ambiguity in the governing documents to allow it to allocate the transaction fees based on each WL Ross-advised fund’s proportionate ownership of a portfolio company, with WL Ross retaining the portion of the transaction fees allocable to any co-investor’s relative ownership share. The SEC alleged further that each WL Ross-advised fund would have received a greater allocation of | WL Ross also voluntarily reimbursed the private equity funds, with interest, $11,873,571 in management fee credits resulting from its retroactive application of the revised allocation methodology to the inception of the funds. | |||

====== 2-306 ====== | ||||

transaction fees had WL Ross excluded the co-investor’s ownership percentage when allocating the transaction fees. According to the SEC, under the allocation method used, WL Ross received approximately $10.4 million in additional management fees from the WL Ross-advised funds between 2001 and 2011. In determining to accept WL Ross’ offer, the SEC considered remedial acts undertaken by WL Ross and cooperation afforded the SEC staff. In particular, WL Ross voluntarily revised its fee allocation methodology to exclude the ownership interest of co-investors, and self-reported the transaction fee allocation issue to the SEC. This case is noteworthy as another example of the SEC’s continuing focus on the fees charged by private equity advisers to portfolio companies. | ||||

8/23/16 | Alleged Failure by a Private Equity Firm to Disclose Conflicts of Interest Related to Fees and Expenses Alleged Failure | In Apollo Management V, L.P., Advisers Act Release No. 4,493 (August 23, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against four private equity fund advisers: Apollo Management V, L.P., Apollo Management VI, L.P., Apollo Management VII, L.P., and Apollo Commodities Management, L.P. (collectively, “Apollo”), each an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, for allegedly failing to disclose certain conflicts of interest relating to monitoring fees paid by | The SEC alleged that Apollo violated Sections 206(2) and 206(4) of, and Rules 206(4)-7 and 206(4)-8 under, the Advisers Act. | Apollo agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, and to pay disgorgement of $40,254,552 and a civil money penalty of $12,500,000. |

====== 2-307 ====== | ||||

to Supervise Expense Reimbursement Practices | fund clients to Apollo, and to supervise a senior partner who improperly charged personal items to Apollo-advised funds. According to the SEC, each fund advised by Apollo owned multiple portfolio companies, each of which agreed to pay monitoring fees to Apollo for providing management, consulting, and other services. The SEC alleged that Apollo’s monitoring agreements with the portfolio companies commonly covered a ten year period and provided for acceleration of monitoring fees when triggered by certain events such as the private sale or initial public offering of a portfolio company, in which case Apollo would receive a present value lump-sum payment of the remaining years under the agreement. According to the SEC, Apollo disclosed to the funds and investors in the funds before investors committed capital that it had the ability to collect monitoring fees, but Apollo did not fully disclose to the funds or the funds’ investors its practice of accelerating monitoring fees until after Apollo had received the fees. The SEC alleged that Apollo’s receipt of accelerated monitoring fees created a conflict of interest that was not fully disclosed, and that prevented Apollo from effectively consenting on behalf of the funds to its receipt of accelerated monitoring fees. The SEC alleged separately from the facts relating to Apollo’s charging of monitoring fees that a general partner of an Apollo-advised fund entered into an agreement in 2008 with a fund and four parallel funds under which the funds loaned the general partner approximately $19 | |||

====== 2-308 ====== | ||||

million, which was equal to the carried interest owed to the general partner. The SEC alleged that the loan was designed to defer the taxes owed on the carried interest by the investors in the general partner. According to the SEC, the funds’ financial statements noted the loan, but failed, until March 2014, to disclose that the loan’s accrued interest would be allocated solely to the capital account of the general partner. The SEC alleged further, and separate from the facts noted above, that, between 2010 and 2013, a former senior partner at Apollo improperly charged personal items and services to Apollo-advised funds and the funds’ portfolio companies. According to the SEC, Apollo first discovered the partner’s improper charges in 2010 and then again in 2012 but failed to take any remedial steps or disciplinary action beyond a verbal warning to the partner after the partner had reimbursed Apollo. The SEC alleged that Apollo’s response to the partner’s conduct demonstrated a failure to appropriately supervise the partner. According to the SEC, Apollo failed to reasonably implement policies and procedures to prevent the above alleged conduct. In determining to accept Apollo’s offer, the Commission considered remedial acts taken by Apollo and cooperation afforded the Commission staff. In particular, Apollo initiated several reviews of the former partner’s expenses and voluntarily reported the improperly charged personal expenses to the Commission staff. | ||||

====== 2-309 ====== | ||||

8/15/16 | Alleged Failure by a Registered Investment Adviser to Disclose Conflicts of Interest Alleged Misappropriation of Client Assets by Investment Adviser Representative Alleged Failure to Supervise Investment Adviser Representative | In Fortius Financial Advisors, LLC, Advisers Act Release No. 4,483 (Aug. 15, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Fortius Financial Advisors, LLC (“Fortius”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, Fortius’ managing member, and a former investment adviser representative of Fortius, for allegedly failing to disclose conflicts of interest and misappropriating client assets. According to the SEC, Fortius was the investment adviser to two trust entities established to manage the assets of an elderly client who was in poor health and suffering from dementia, with the understanding that the assets would be distributed to a charitable foundation upon the client’s death. The SEC alleged that the Fortius investment adviser representative acted as trustee to the trusts pursuant to a separate service agreement between the client and the representative. According to the SEC, during the period from 2006 until 2008, Fortius invested the trusts’ assets in traditional securities such as publicly traded stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, for which it charged an asset-based fee of between 1.0% and 1.5%. The SEC alleged that, during the period from 2008 until 2009, Fortius began to invest the trusts’ assets in unsuitable, illiquid investments in which Fortius had an undisclosed financial interest. According to the SEC, Fortius invested $500,000 of the trusts’ funds into one of Fortius’ private fund entities, | The SEC alleged that Fortius, Fortius’ managing member, and Fortius’ investment adviser representative willfully violated Section 206(2) of the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that Fortius willfully violated, and its managing member caused its violation of, Section 206(4) of, and Rules 206(4)-2 and 206(4)-7 under, the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that Fortius willfully violated, and its investment adviser representative caused its violation of, Section 207 of the Advisers Act. | Fortius, Fortius’ managing member, and Fortius’ investment adviser representative agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges. Fortius and Fortius’ managing member agreed to censure. Fortius agreed to pay disgorgement of $24,070, and a civil money penalty of $70,000. Fortius’ managing member agreed to pay disgorgement of $1,969, and a civil money penalty of $25,000. Fortius’ investment adviser representative agreed to be barred from association with, |

====== 2-310 ====== | ||||

which charged a higher asset-based fee of 2% to 2.5%. The SEC alleged further that Fortius caused the trusts to loan approximately $245,000 to two private companies in which Fortius had a large financial stake. According to the SEC, Fortius, its managing member, and its representative, had a financial incentive in each of these transactions creating several conflicts of interest. The SEC alleged that the Fortius representative’s conflicts of interest prevented him from effectively consenting to these transactions on behalf of the trusts as trustee. According to the SEC, Fortius’ investment adviser representative misappropriated approximately $137,000 from the trust accounts over a four-year period. The SEC alleged that this misappropriation indicated that Fortius failed to appropriately supervise the representative and to adopt policies and procedures reasonably designed to prevent this conduct. | The SEC alleged that Fortius’ investment adviser representative willfully violated Section 206(1) of the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that Fortius and Fortius’ managing member failed reasonably to supervise Fortius’ investment adviser representative within the meaning of Section 203(e)(6) of the Advisers Act. | among others, any broker, dealer, investment adviser, or municipal adviser. | ||

8/12/16 | Federal Court Decision Relating to Advisers Act’s Definition of Compensation | In United States v. Everett C. Miller, No. 15-2577 (3d Cir. 2016), Everett C. Miller, a formerly registered investment adviser representative under New Jersey securities law, appealed his sentence after being convicted in a criminal proceeding of securities fraud and tax evasion in connection with a Ponzi scheme he allegedly orchestrated by selling “promissory notes” through unregistered offerings. Mr. Miller entered into a plea agreement and cooperation agreement in which | Mr. Miller pled guilty to one count of securities fraud, 15 U.S.C. § 78j(b), and one count of tax evasion, 26 U.S.C. § 7201. | Mr. Miller was sentenced to 120 months in prison. |

====== 2-311 ====== | ||||

the government agreed to recommend a reduction in the length of Mr. Miller’s prison sentence under the applicable sentencing guidelines in exchange for Mr. Miller’s acceptance of responsibility. A Federal District Court granted the penalty reduction, but also imposed on Mr. Miller a penalty enhancement applicable to an “investment adviser.” The issue before the Court was in effect whether Mr. Miller met the definition of an “investment adviser.” Mr. Miller argued on appeal before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (the “Third Circuit”) that the District Court’s application of the investment adviser enhancement was in error, because he was not an investment adviser as that term is defined in Section 202(a)(ll) of the Advisers Act. In particular, Mr. Miller argued that he did not provide securities advice “for compensation.” The Advisers Act does not define compensation, but the SEC has interpreted the term broadly to include any direct or indirect benefit, including the reimbursement for services performed or costs incurred. Mr. Miller argued that he did not receive any compensation because he was not reimbursed for services performed or costs incurred, and he did not collect a management or incentive fee from purchasers of the promissory notes. The Third Circuit rejected Mr. Miller’s argument and held that the “for compensation” requirement in Section 202(a)(ll)’s definition of investment adviser was satisfied “when he commingled investors’ accounts and | ||||

====== 2-312 ====== | ||||

spent the money for his own purposes.” This case is particularly noteworthy as the Third Circuit’s holding that compensation for the purposes of the definition of an investment adviser included the economic benefit Mr. Miller received from misappropriating assets appears in effect to expand the reach of the definition. | ||||

7/21/16 | Alleged Materially False and Misleading Statements made by a Registered Investment Adviser to Clients in Connection with Common Stock Offering of Adviser’s Parent Company Alleged Failure by Adviser to Implement Policies and Procedures to Ensure Parent Company Stock | In Concert Global Group Limited, Advisers Act Release No. 4,459 (July 21, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Concert Global Group Limited (“Concert Global”), the parent company of Concert Wealth Management, Inc. (“Concert Wealth”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, and Concert Global’s chief executive officer, arising from alleged materially false and misleading statements made in connection with offerings of Concert Global’s common stock. According to the SEC, Concert Global raised $2.2 million between 2010 and 2013 through sales of its common stock to approximately 21 investors in multiple states, including 12 of Concert Wealth’s advisory clients. The SEC alleged that Concert Global and its chief executive officer provided these investors with private placement memoranda that contained material misstatements and omissions, such as overstating Concert Global’s revenues by as much as 50% and its subsidiaries’ total assets by approximately $1 billion. | The SEC alleged that Concert Global and its chief executive officer violated Sections 5(a), 5(c), 17(a)(2), and 17(a)(3) of the Securities Act. The SEC alleged that Concert Wealth and Concert Global’s chief executive officer willfully violated Section 206(2) of the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged | Concert Global, Concert Global’s chief executive officer, and Concert Wealth agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges. Concert Global’s chief executive officer and Concert Wealth agreed to censure. Concert Global and Concert Wealth agreed to pay, jointly and severally, a civil money |

====== 2-313 ====== | ||||

Offering Documents Provided to Advisory Clients were Accurate | According to the SEC, the private placement memoranda also failed to disclose conflicts of interest arising from Concert Global’s use of the offering proceeds to repay its debt to related entities that Concert Global’s chief executive officer controlled and to pay quarterly dividends to the chief executive officer on his preferred stock. The SEC alleged further that Concert Global and its chief executive officer made these offerings without filing a registration statement under the Securities Act with the Commission or relying on an applicable exemption from registration. According to the SEC, Concert Wealth failed to implement policies and procedures reasonably designed to prevent the above conduct. The SEC alleged that Concert Wealth’s policies failed to address the selling of its parent entity’s common stock to advisory clients or to ensure the accuracy of statements made in connection with such offerings. https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2016/33-10113.pdf In a related case, in Dennis Navarra, Advisers Act Release No. 4,460 (July 21, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Concert Global’s former chief financial officer for allegedly making materially misleading statements and omissions in connection with the offerings | that Concert Wealth willfully violated, and Concert Global’s chief executive officer caused the violations of, Section 206(4) of, and Rule 206(4)-7 under, the Advisers Act. The SEC alleged that Concert Wealth’s former chief financial officer violated Sections 5(a), 5(c), 17(a)(2), and 17(a)(3) of the Securities Act, and willfully aided and | penalty of $120,000. Concert Global’s chief executive officer agreed to pay a civil money penalty of $60,000. Concert Wealth’s former chief financial officer agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the | |

====== 2-314 ====== | ||||

described in the above case. | abetted and caused Concert Wealth’s violation of Section 206(2) of the Advisers Act. | charges, and to censure. | ||

7/18/16 | Alleged Failure by Investment Adviser to Disclose Loans from Broker-Dealer | In Washington Wealth Management, LLC, Advisers Act Release No. 4,456 (July 18, 2016), the SEC settled public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings against Washington Wealth Management, LLC (“WWM”), an investment adviser registered under the Advisers Act, for allegedly failing to disclose conflicts of interest relating to loans it received from a broker-dealer. According to the SEC, in 2012, WWM entered into an agreement with a broker-dealer to provide clearing, custody, and other services for WWM’s clients. The SEC alleged that WWM also received more than $1.8 million in loans from the broker-dealer to cover costs associated with transitioning its business from another broker-dealer. According to the SEC, $1.1 million of these loans were forgivable over a five-year period if the relationship continued during this period. The SEC alleged that for nearly a year after the loans were received, WWM failed to appropriately disclose these loans to investors. During this time, according to the SEC, WWM’s Form ADV, Part 2A brochure under the Advisers Act disclosed its relationship with the broker-dealer and other loans WWM had received, but did not disclose the loans from the broker-dealer. The | The SEC alleged that WWM willfully violated Sections 206(2) and 207 of the Advisers Act. | WWM agreed to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations and any future violations of the charges, to censure, and to pay a civil money penalty of $50,000. |

====== 2-315 ====== | ||||

SEC alleged that the loans created a conflict of interest that should have been disclosed to investors. According to the SEC, the disclosure failure was discovered after the SEC’s Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations (“OCIE”) conducted an examination and informed WWM in July 2013 of its failure to disclose the loans. | ||||